News

News >

Read an extract: The Shortest History of England

Discover the beginnings of Brexit and how the past throws striking light on the present in this extract from The Shortest History of England.

At the 2009 European elections, it was clear for any who wanted to see it that the main parties had taken their core voters too much for granted. Nigel Farage’s UK Independence Party tore into the South, and the all but openly neo-Nazi British National Party took two seats in the North (as did UKIP). But the main parties didn’t see the deluge coming. Their MPs and advisers had been born and bred under the two-party system: it being all they knew, it was all they saw.

And after all, at the General Election of 2010, things looked much the same as ever: it was Outer Britain vs the South again, with the only news being that the Conservatives were still a bit toxic, so enough southerners voted Liberal to create the first ever Lib-Tory coalition.

This southern alliance embraced austerity as the cure for the Great Crash, turning off the public spending tap. Since this had primarily been used to pump money into the Outer UK, the impact was greatest there.

The long-planned opening ceremony of the London Olympics (2012) tried to express the idea of a U.K. at ease with itself. Really, though, it was an elegy. Together, New Labour and the Coalition had accidentally created a new constellation which gave the southern and northern English real things in common.

The new army of English voters-in-waiting created by Cool Britannia, EU immigration, austerity...

Two Englands, One Party

But would the angry English, North and South, ever vote as one? In the second decade of the new millennium, their allegiances were as tribal as ever.

The Labour north and Conservative south make England look ever more like two nations… cultural and political identities are ever more distinct.

Economist, 18 September 2013

Even the protest vote was split North/South: the only place where both the BNP and UKIP were at peak strength was Essex, which became the capital of Brexit (Danny Dorling).

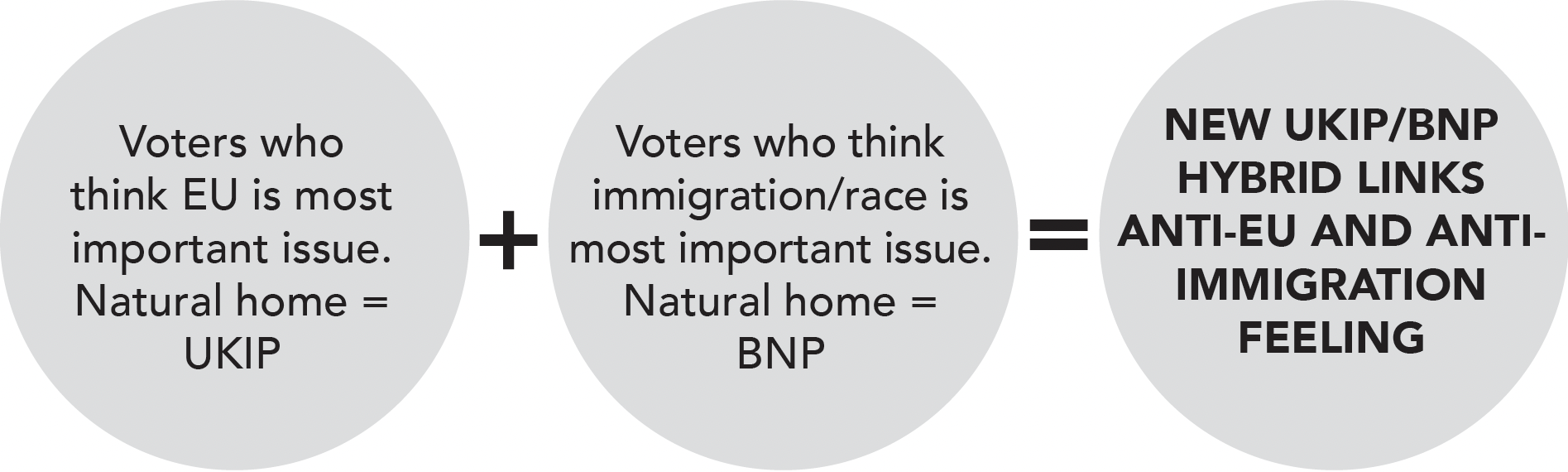

Farage showed the way. His UKIP had hit a glass ceiling because the EU wasn’t a burning issue to enough people. Immigration, though, was another story. In 2012, the BNP destroyed itself in faction-fighting, and he went after its voters. The new hybrid BNP/UKIP piggybacked its niche obsession onto the mass worry, and crossed the old divide.

UKIP’s surge… has relatively little to do with the public’s hostility to Europe, an issue which never makes the top 10 of their daily concerns.

Financial Times, March 2013

Daniel Hannan, the Tory MEP whom the Financial Times would later call the brains behind Brexit, saw that Farage had cracked it. The anti-Europeans, who had been plotting vainly for two decades, had their English foot-folk at last. Hannan proposed a UKIP/Tory pact – and entirely rewrote his anti-EU story.

The original 1990s version was all about an ideological crusade for unfettered capitalism. It hadn’t played to voters then and it wouldn’t play to Farage’s New Model Army: most of them just wanted stable communities who spoke English, with less competition for jobs, affordable housing and GP appointments. So the script was changed. Leaving the EU was no longer about all the British going boldly off aboard the USS Free Enterprise. Instead, it was last-ditch cultural class-war between the English and the elite collaborators of a European occupation.

In the 1990s, the anti-EU rebels had hymned freebooting, ocean-spanning British capitalism; now, they went after a defensively-minded working-class audience, and they changed their story to one of English resistance.

14 October 1066: England’s Nakba. Harold Godwinson, the last Anglo-Saxon king, fell in battle, opening the door to occupation and feudalism

7:55am, Oct 14 2015, Daniel Hannan on Twitter

The English, Hannan wrote, had brought Liberty with them from deep in the German woods until, with the Conquest, Englishness became, almost by definition, a badge of poverty and subjugation. Within living memory, he claimed, Royal Navy sailors assumed that, being upper-class, the Admiral was likely to be more sympathetic to the French. The EU was just the latest continental dictatorship to be inflicted by a collaborating elite on the hapless English.

Cultural class war, according to Daniel Hannan

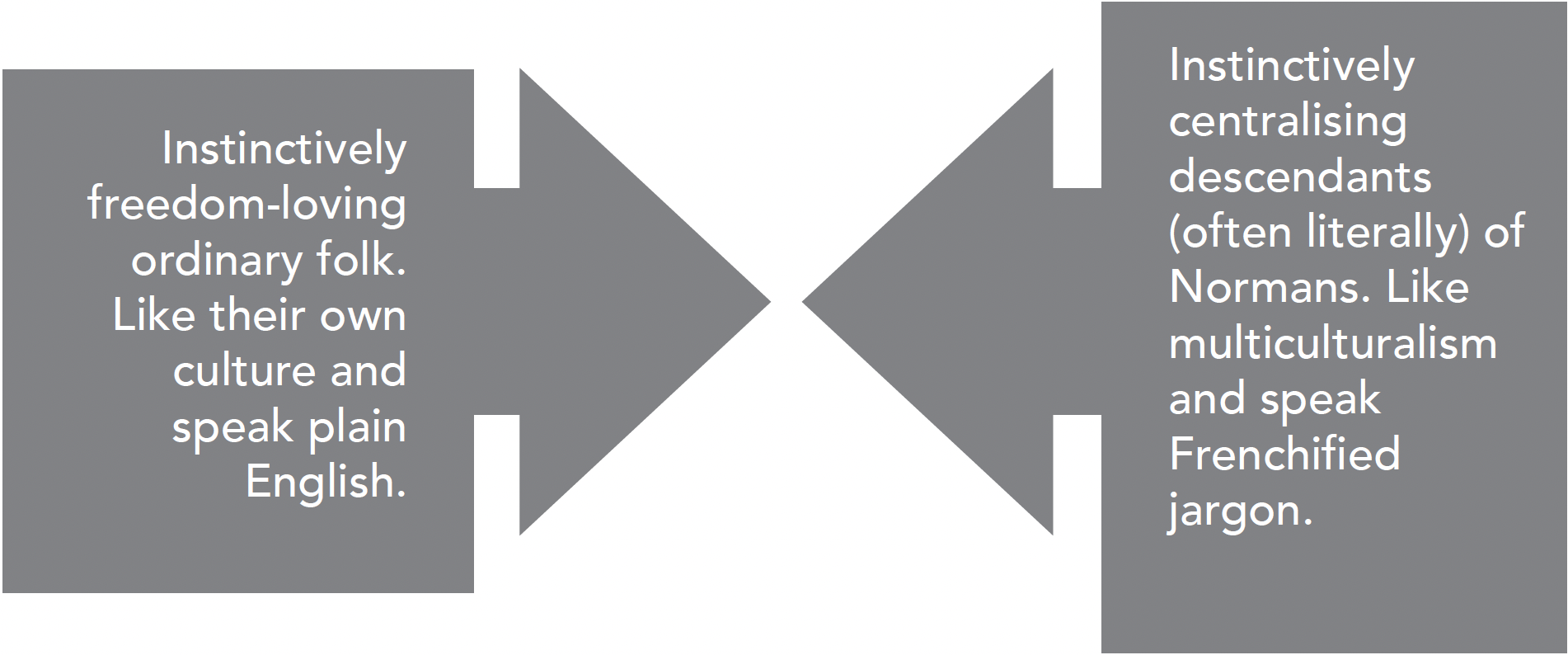

Like all effective rabble-rousing, it worked because it had a germ of truth. The daily, lived experience of the ordinary English, generation to generation, was that they were ruled by an elite who spoke differently.

Almost 1,000 years after the Normans took power in England, the language of power (parliament, government, civil service, police, court, judge) the military (army, navy, soldier, battle, campaign) and finance (interest, rent, money, tax, mortgage, asset, property, inheritance) retains a strong French cast… Anglo-Saxon-derived words still make up the lexis of the everyday.

James Meek

In 2013, an extraordinary study, published by the London School of Economics, showed just how alive that history was. Researchers put the names of students in the ancient and modern records of Oxford and Cambridge through algorithms which tracked status persistence. It turned out that nothing – not the Black Death, not the Reformation, not the Industrial Revolution, not two World Wars – had seriously disrupted the elite since records began, in the late 1100s. The Daily Mail boiled it down:

1,000 years after William the Conqueror invaded, you still need a Norman name like Darcy or Percy to get ahead

Daily Mail

Small wonder that when the rebel elite told their new tale of why the EU was evil, the ordinary English, feeling under siege by change, immigration and austerity, were ready to believe it.

Share this post

About the author

James Hawes is the author of The Shortest History of England and the internationally acclaimed The Shortest History of Germany. His other works include Englanders and Huns: The Culture-Clash which Led to the First World War, Excavating Kafka and Speak for England (2005), which predicted Brexit and has been adapted for the screen.

More about James Hawes