News

News >

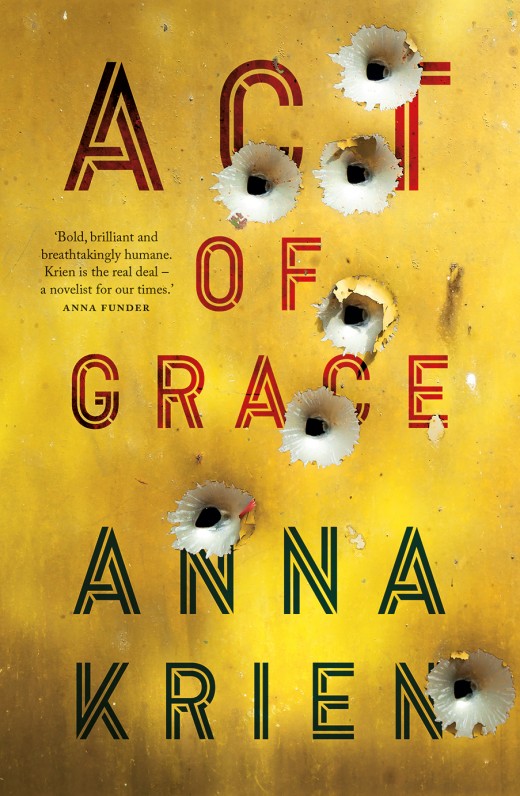

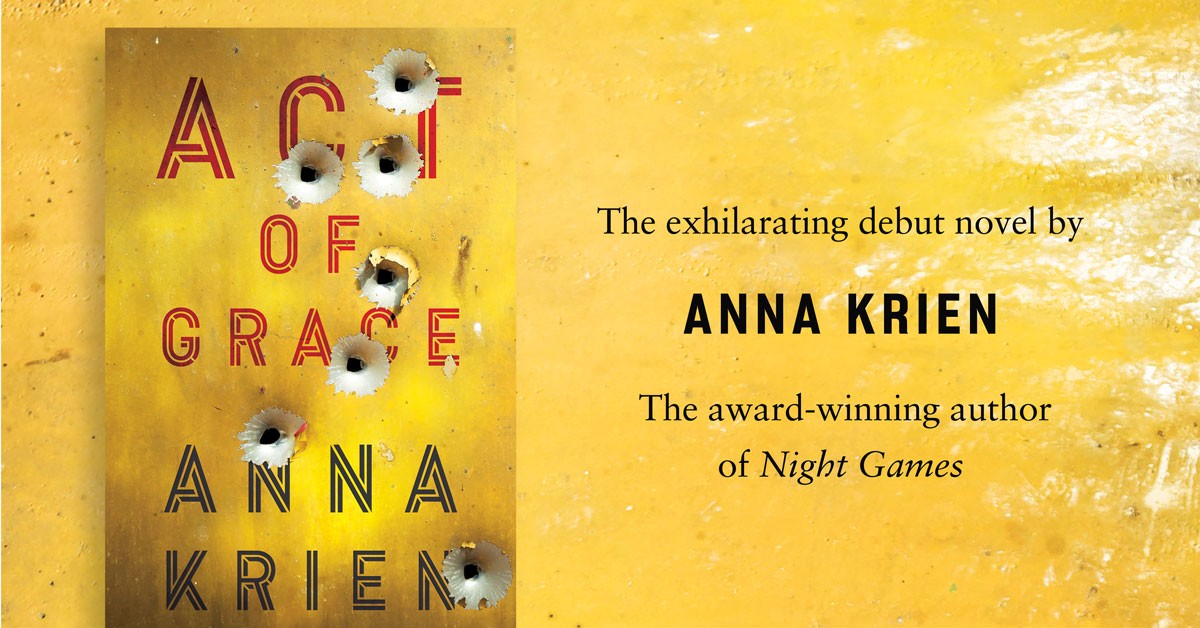

Act of Grace: extract

Read an extract from Act of Grace, the debut novel by Anna Krien.

Sorry Rocks

So much for being in the middle of nowhere, Robbie thought as she stood to watch the flashing blue-and-red lights speed down the strip of bitumen towards them.

‘They’re coming,’ Viv yelled to the boys staggered on the eastern slope of the massive rock, heads down, ears filled with the roar of blowtorches. The wail of the sirens saw sections of the desert light up: fancy canvas domes, tarpaulin mansions and tiny taco tents glowed. The headlamps of backpackers in their swags collided like lasers in the night. Someone had called it in, a mysterious spatter of orange sparks spilling down the side of Uluru.

Lifting his thumb from a blowtorch, Charlie pulled up his goggles. He was drenched in sweat.

‘It’s cool, Charlie,’ Jay called. Charlie nodded slowly and pulled down his goggles. Digging out a lighter from his shorts, he relit the torch, his tongue poking from the corner of his mouth in concentration, bringing flame to metal.

*

Charlie was a big guy, shy. Seventeen years old. Past initiation age, but the elders hadn’t put him through ritual yet. He hung with the younger teenagers in the community: Jay, Reg, Rose, Viv and Jez. The kids Charlie’s age were too fast – driving, having sex. Some already doing time. ‘He was an alcohol baby, Charlie was,’ Eileen told Robbie. ‘You can hear them in the early morning: when the community is still and quiet, they start up bleating like sick lambs.’ Charlie sometimes worked in the art room where Robbie was assisting Eileen, who managed the remote community’s art program. ‘He’s a beautiful painter,’ Eileen said, ‘but only if you intervene in time.’

When Robbie first saw Charlie make art, she was mesmerised. He played with the paint like the younger kids played with fire and spinifex in the evenings, pulling the long grass from the dirt and light ing it, fearlessly winding it around their fingers like a cat’s cradle, hands swifter than the flame. Charlie seemed to knit the hues onto the canvas just like that. Often, he’d be painting so briskly that he’d grab a second brush to use in his other hand. As though each colour were a note, he’d create a melody – from the bottom of the canvas a landscape would rise out of shadows he had already laid down. Then, after a time, Charlie would fling aside the brushes and use his fingers to push the paint around.

At this point, Eileen would get ready to slide between him and the canvas. ‘That’s enough now, Charlie,’ she’d say in a singsong voice, and he would look at her, bewildered, as if emerging from a trance. Then he’d nod, letting her take the painting away.

Robbie had been left in charge one day when Charlie was painting, and she’d been so absorbed watching him – his large clumsy body hardened to a single focus, the painting forming like photographic paper in a chemical bath – that she forgot to step in. At first, she didn’t notice his fingers start to push the paint more fiercely, only that the sky seemed to churn. Then he pressed his palms flat, making wide circles, building boulders before skidding them outwards.

‘Charlie?’ Robbie finally said, but it was too late. He grunted and pushed her away with his shoulder as though they were on the football field. He put his face close to the painting, peering into it, hands working harder until it was just a mess of brown, a shit-coloured storm.

‘Charlie?’ Robbie said, worried for him. He stopped, body heavy again, arms by his side, muddy hands dangling. He was panting, struggling to control the rise and fall of his chest. He hung his head. ‘Sorry,’ he said quietly. Robbie saw he had bitten his tongue, bright red pooling on pink. He looked so sad that she had to fight the urge to hug him.

But on her second day in the remote community, the cultural relations officer, Quinn, had told her that showing affection was inappropriate. ‘These are traditional people, you know. An ancient desert culture, very conservative.’ He had looked at her T-shirt, eyes on her breasts. ‘I’d suggest a looser-fitting shirt as well.’ Robbie set her jaw. Quinn was a prick. She had figured that out almost instantly.

In his office, he sat close, pulling his chair around. He told her he had a skin name given to him by the local people and had witnessed ceremonies he was not permitted to talk about.

‘Then why are you telling me?’ Robbie asked, and he sat back, sizing her up.

‘There’s hierarchy out here,’ he said. ‘It’s best you know where you’re placed.’

In hindsight Robbie wished she had walked out of his office then, told him to piss off, but she was already learning that the tyranny of distance meant having to rely on all manner of pricks.

Still, Robbie wasn’t acclimatised enough to call Quinn’s bluff on hugging. Instead, looking at the wrecked canvas, she said unconvincingly, ‘I like it,’ but Charlie was slow, not stupid. He made a muffled noise as he got up to leave, wiping his hands on his pants. Robbie thought about a couple of the babies she had seen, the ones born from briny alcoholic wombs, their limbs scrawny, chests caved in. Their constant bleating, always thirsty. Born with a hangover. She tried to imagine the ache in their heads, how the light of day glared at them. The health workers, when they flew in, focused on the alcohol babies: took their measurements, gave them shots, revised their formula, shushing them when they arched their backs, tiny furious bodies opening and closing like scissors.

She tried to imagine Charlie as a baby: shrivelled and grey, bulbous in the wrong places, thrashing in the heat. There was a gracelessness about him; he walked as if he’d made numerous adaptations to cope, one shoulder lurched forward, neck crooked, eyes on the ground. It was only when painting that he briefly found his grace.

Eileen was annoyed that Robbie hadn’t intervened in time to rescue the painting. ‘You have to grab it before he does this,’ she said tersely as she wet a sponge, rubbing as much paint off the canvas as she could. ‘He doesn’t paint anywhere near as much as he needs to make a living.’ Robbie nodded, watching. There was something sad about Charlie’s painting being washed down the drain, even though it was mostly awful to look at.

‘Charlie!’ Reg yelled, and Charlie’s head jerked up, Robbie’s too, both looking to the rock where Reg was working. ‘Faster, man!’ Reg yelled. Charlie nodded, fumbling a little under pressure. You can tell a novice, Robbie’s metalwork tutor had said to her class once, by an excess amount of slag and sparks. The night was thick with an orange storm of slag, the sparks blowing up into the boys’ faces, flecking their bare arms and legs with rice-sized burns. Charlie had started at the bottom of the chain, Reg at the top, and Jay was going between them, delivering fresh butane canisters from his backpack. He also had Robbie’s orange Makita speaker with him and was picking the tunes.

Two more cop cars had appeared, catching up with the first one, and when they got closer, Jay ditched the Detroit beats and fiddled with his MP3. ‘Hold up, Reg!’ he yelled. ‘Listen up! Charlie!’ The teenagers cocked their heads to listen, the girls too. There was the scratching sound of vinyl and then the beat kicked in. Jez, Rose and Viv leapt to their feet, grinning. Reg laughed and held his blowtorch up in the air, shooting a flame off into the sky.

‘Right about now!’ yelled Jay, and Charlie held up his arms, wagging his palms to the beat.

‘Judge Dre presiding,’ Charlie bellowed, a big shiny grin on his face as the girls cheered.

‘Order, order, order,’ Jay sang. ‘Ice-Cube, take the muthafucken’ stand!’

Then they all chimed in: ‘FUCK THA POLICE!’

Robbie started to laugh, an awkward, gulping kind of laughter. She shouldn’t be here. As soon as she realised what they planned to do she knew she was up shit creek, but by then it was too late. Now Robbie watched the six teenagers with their determined faces, full of fuck you. They had a plan – a plan, something with a past, a present and a future. Something she had most days without even realising it. Robbie wondered if it was the first time for these kids.

*

Earlier in the evening Robbie had caught Jay trying to nick her speaker. Bullant had been asleep in a cardboard box at her feet and suddenly the puppy’s black ears pricked and he scrambled out to catch Jay in the act. When Robbie followed, she found Bullant licking Jay’s legs and saw the other kids waiting at the open door of the arts centre, although she’d clicked it locked two hours ago.

‘We’ll bring it back,’ Jay said, and picked up the speaker. It was paint-spattered, covered with protest stickers.

Robbie put up her hand. ‘Ah, no fucking way, Jay.’

He glared at her. When he saw she wasn’t going to budge, he went back to the group at the door, all of them talking in language – Pitjantjatjara probably, Robbie still couldn’t tell. She pulled on her boots and a jumper while they argued, Bullant excited, clawing at her jeans. ‘How about this?’ she said, when she was ready. ‘You can borrow it if I come with you.’

The six teenagers fell silent and stared at her. Robbie flashed Viv a smile and Viv did a small, almost secret wave, flicking her wrist out from her hips.

‘No,’ Reg said firmly. He was the leader, tall and lanky, a good footy player. He turned and began to walk away.

‘Please?’ Jay said to Robbie, staring longingly at the speaker. She shook her head. ‘Only if I come.’

Jay kicked the ground fiercely. ‘Fucking gubba,’ he muttered. Robbie didn’t say anything, just arched an eyebrow. Viv said something in language to him. ‘Sorry, Miss,’ he finally mumbled, and Robbie shrugged. ‘Don’t worry about it.’

Jay ran off then, and caught up with Reg. Jay talked fast, gesturing. Viv split next, joining Jay, talking too and pointing at her. As they spoke, Reg studied Robbie. His gaze was intense. She knew from seeing him at the swimming pool (‘No school, no pool’ was the mantra) that his chest was still smooth, not yet nicked with scars. His black hair was woven into cornrows, African-American style. He wore basketball gear – a red satin singlet, baggy black shorts, high white socks stained pink by dirt, and black sneakers. His skin, like many Anangu, reminded Robbie of kelp, brown but seemingly lit orange from within. Odd, she had thought when she first arrived, to gaze at the skin of a desert people and think of the sea.

‘Okay,’ Reg said finally.

Jay spun around, grinning. He gestured to her and the others impatiently. ‘Come on.’

Robbie hefted the speaker onto her hip and whistled to Bullant. Already the teenagers had begun to fold into the night. She rushed to catch up when they suddenly doglegged off the street and into the scrub. Robbie followed, but within seconds she’d lost them. She stared hard at the dark. A few outlines formed, waiting at the tall wire fence that stretched around the community. Most had already wriggled under it. Viv was holding the bottom of the fence up, waving at Robbie to hurry.

Share this post

About the author

Anna Krien is the author of the award-winning Night Games and Into the Woods, as well as two Quarterly Essays, Us and Them and The Long Goodbye. Anna’s writing has been published in The Monthly, The Age, Best Australian Essays, Best Australian Stories and The Big Issue. In 2014 she won the UK William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award, and 2018 she received a Sidney Myer Fellowship. Act of Grace, her debut novel, is out now.

More about Anna Krien