News

News >

Are factories the answer to America’s great divide?

To defeat populists, build new factories, says Dennis Glover, author of Factory 19.

Watching CNN on Wednesday evening, the name of one of the late reporting voting districts in Pennsylvania caught my eye: Allentown. You might remember it from that great Billy Joel hit of the early 1980s about the beginnings of the rustbelt in the American north-east:

Well we’re living here in Allentown

And they’re closing all the factories down

Out in Bethlehem they’re killing time

Filling out forms

Standing in line

As those who know the song will remember, it goes to say how, once their jobs were taken away, these factory workers had the flag thrown in their faces.

In 2016, these disrupted people and their children helped Trump break the Democratic blue wall of Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin and create Trump’s base. They felt betrayed.

And it’s no wonder. Such people – the ones at Trump’s mask-less rallies – were once the most affluent working class on Earth – producers of beautiful cars (tell me you’ve never lusted after a Corvette or Cadillac), the steel they were made from and the coal that turned iron ore into all that steel. They’re not all poor – some cling on to the remnants of those old industries – which is why they can afford those big SUVs that tried to push the Biden–Harris campaign bus off the freeway. But many are. They reach for their OxyContin to relieve the pain of their broken backs, and others reach for bourbon or, in extremis, crack cocaine, to drown out the hurt and sorrow of a way of life destroyed. America let them down. Even though he was probably laughing at them behind their aching backs, Trump at least pretended to care about their economic distress.

Now that it looks likely Donald Trump has been defeated, the populist nightmare is over, right? We can only hope so. But what if this only round one?

Think about it. Trump’s supporters are still there and still numerous – still about 47 per cent of the American electorate. And my guess is that unless President Biden can address their anger they’re likely to be open to the same basic, angry populist messages. Trump himself can run again in 2024, unless of course he’s in jail. Or maybe he’ll be replaced by a new populist candidate who is luckier, smarter or even more ruthless.

Best therefore not to concentrate on what’s gone – the old Trump – but what’s still there: Trump’s base.

How should we respond? This is a crucial question, both in the United States and in Australia, because what the last four years have proved is that if you impoverish and alienate proud working-class communities, you cause mayhem by creating the ground for right-wing populism to succeed. Think about Pauline Hanson’s rise and re-rise over the past 25 years. (She came back too, remember, even after they put her in jail.) And think of the problems being faced nationally by the ALP, which is trying desperately to hold on to its diminishing blue-collar base.

Maybe instead of denouncing Trump’s supporters as idiots and dupes, we should try to win them back to democracy by rebuilding their jobs and their communities.

There are many industries in which jobs can quite easily be created. Childcare and aged care come to mind. But there are other industries that would likely be welcomed with even greater enthusiasm – in manufacturing. This idea, of rebuilding manufacturing, is the one most likely to close the class-based fractures that are weakening our political system.

I’m saying let’s rebuild the manufacturing industries that once made blue-collar regions and suburbs of Australia so affluent and productive. Dandenong, Doveton, Broadmeadows, Elizabeth and other places weren’t always places of high unemployment. They once had well-paid, unionised manufacturing jobs, and plenty of them.

This isn’t just about jobs and money, though.

Factories are special places. They draw people together in large numbers, give them purpose, unity, self-confidence – and democratic power. Running factories needs skills, cooperation and a common purpose.

You can’t run factories with gig labour, minimum wages and winner-take-all industrial relations. A good factory has a great canteen selling nutritious and tasty food, on-the-job training, career advancement opportunities, an annual children’s Christmas party and intelligently led unions.

Today, professional people get all these employment benefits as a matter of course. Law firms, schools and insurance companies offer them to attract and keep good staff. But working-class people are increasingly denied them. Often, employed through labour contractors, they’re not even sure who their legal employers are.

What I’m saying is that there’s something inherently democratic – social-democratic, to be more precise – about factories and manufacturing in general. By offering working-class people a stake on our success and the means to advance themselves, they help keep dangerous populists at bay. It’s no coincidence that that modern democracy followed the Industrial Revolution, and that the most stable, affluent and egalitarian era of modern history was during the great manufacturing-led post-war boom.

So what would such factories make? The COVID-19 pandemic displayed the brittleness of the global manufacturing supply chain, especially for important drugs and medical supplies. With the world now moving inexorably towards carbon neutrality by mid-century, there is a major opportunity to manufacture high- and low-tech sustainable technologies. With production costs in China rising along with affluence, why not build wind turbines, solar panels and other energy efficient technologies here? Until recently, we made cars, remember? Why not electric ones?

The best way to defeat populism is to take away the economic grievances that are feeding it. And the best way to do that is by giving working-class people better jobs – including in factories.

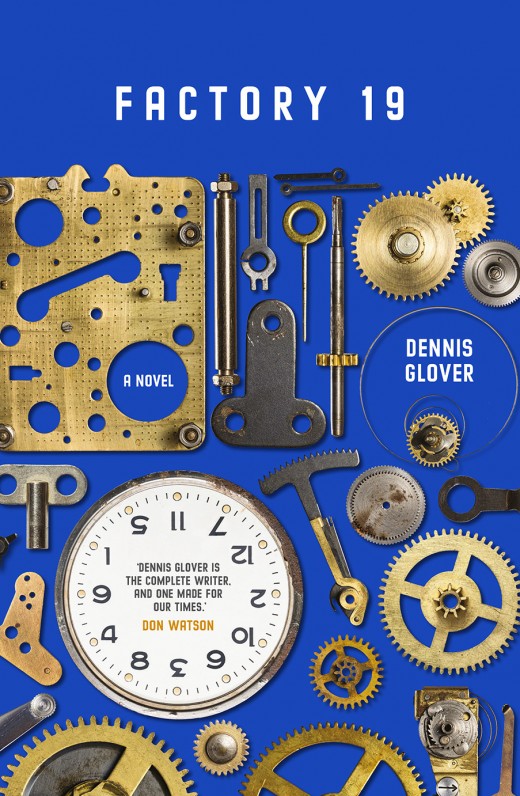

Dennis Glover’s new novel, Factory 19 – about the re-creation of the factory world – is out now.

Photo by Pierre Châtel-Innocenti on Unsplash

Share this post

About the author

Dennis Glover was educated at Monash and Cambridge universities and has made a career as one of Australia's leading speechwriters. His first novel, The Last Man in Europe, was published around the world in multiple editions and was nominated for several literary prizes, including the Walter Scott Prize for Historical Fiction. His second novel, Factory 19, was published in 2020, and his third, Thaw, in 2023. His book-length essay An Economy Is Not A Society was …

More about Dennis Glover