News

News > Extract

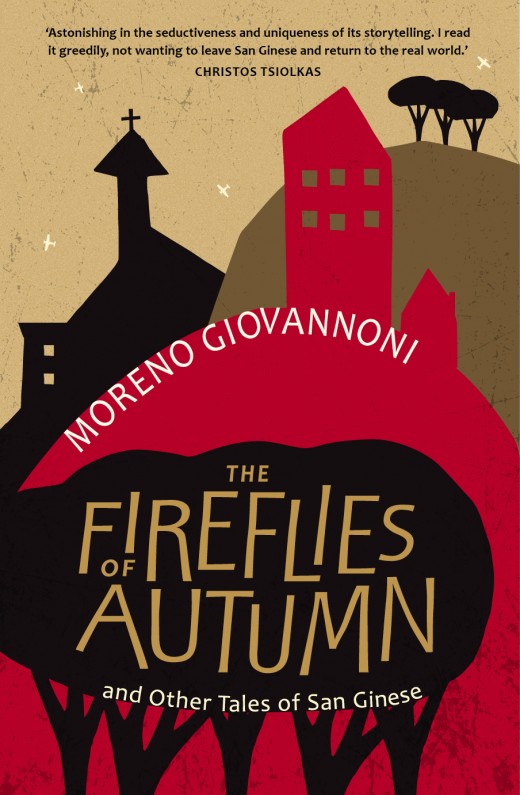

Feature extract from The Fireflies of Autumn

The Fireflies of Autumn tells of San Ginese, a village in Tuscany, and its rich, sometimes tragic life. Written by Moreno Giovannoni, the inaugural winner of the Deborah Cass Prize, The Fireflies of Autumn is now available for pre-order.

The Percheron

Listen to me and I will tell you a story about the days when there was poverty in San Ginese and we used to go to America to work and make our fortune. I will try my best to tell it well, with the skilful use of words and some feeling from my heart.

At the age of twenty-four my father, Vitale, started working for the Madera Canyon Pine Company in California as a whistle punk. From whistle punk he was promoted to teamster. His favourite horse was a docile, intelligent giant of an animal, a French Percheron.

The Percheron waited patiently for the man to tell him when to start pulling, when to stop, when to back up. Vitale, who had been living at an Italian working men’s hotel in Fresno before moving to the logging camp, spoke no English. He was lonely in California and missed his family and the life of the village, so the horse was a welcome companion.

Although there was a good camaraderie between the men in the camp, and the team even included some Italians from north of Venice, near the Austrian border, who were expert timber-cutters and tree-fellers, Vitale was most at home with his loyal Percheron. He was what was known then as a proper Tuscan peasant and knew the proper Tuscan peasant’s work. This meant he was used to working with animals, in particular the cows back in the village that pulled the hay carts and ploughs and gave milk that was made into butter and cheese, and every year gave birth to a calf that could be sold. The stable near the back door of the kitchen at his father’s house always housed one or two cows and their calves.

Now that he was responsible for looking after a horse – feeding it, grooming it, making sure it was strong and healthy and happy and ready to pull the log, stop or back up – Vitale was proud. He was the whistle punk when he first started, as this was the work they gave to young or inexperienced men, and he was proud of his promotion to teamster. In San Ginese only rich people owned horses, and looking after this horse made him feel rich.

He was happy that he could at least feel rich, as his American adventure had not been as successful as he had hoped it would be. In seven years he had earned a living but had not made his fortune. That would come soon, but he did not know it yet. He intended to return to San Ginese when the time was right and marry. Marriage too would come, but in the pine forest that day he was reflecting on his bad luck and felt disappointment and frustration.

The day before the incident, government officials visited the logging camp and asked him and the other men a lot of questions. The officials completed a registration card with all his details. They asked him whether he claimed exemption from the military draft, and he said he did claim it. He did not want to join the army because he wanted to look after his mother and father (or ‘folks’, as the American official wrote on the draft card). This was not the only time they had come looking for him, and he was always worried that they were going to conscript him. He managed to lie low, and on a few occasions when he felt it would be safer to hide, he hid. Even his employers helped to hide him, so that after the war he was able to return to San Ginese without serving in the army of the United States of America.

As he was reflecting on his poor American luck, he was also troubled by this official visit. Thoughts of bad luck and ominous officialdom chased each other through his head and gave him no rest the night before the incident.

On that day the Percheron was reluctant to follow the man’s instructions. He sensed the man was distracted. The Percheron waited to be acknowledged, for his presence to be appreciated. Just a word, a friendly tap on the shoulder. He could not work unless he sensed a partnership between himself and the man. Then he realised that not only was the man distracted but that he was too. He could no longer read the signals coming from the man. He didn’t know whether he was being asked to pull or stop or back up. Having failed to establish the working rapport, he tried very hard to continue without it, but kept getting it wrong. And yet they had worked together for several months now. The horse loved the man and responded well to him: he sensed that the man was an experienced handler of draft animals, although the horse didn’t think of himself in those terms exactly. He thought of himself as himself.

Vitale knew that the only way to work with a horse was to use a psychological approach, because a man’s strength cannot match that of a horse. He tried to anticipate the horse’s behaviour and gently encouraged responses consistent with the needs of the work. So what happened that day was a shock to both the man and the horse. Vitale was surprised to learn that he was capable of such a thing, he who in his later life – as he grew to be very old – would have a reputation in the village and the surrounding district for his gentleness of manner and whose son would tell stories to his grandchildren about their gentle grandfather. When the village spoke about him decades later, mention was also made of his father, Tista, from whom the mild manners were inherited, and how the gentle nature was in the blood of the family.

Vitale spoke to the horse and tugged and tapped him in the usual way, and the Percheron did not move. Vitale called out again, louder, and shook the reins. The horse tried to back up.

Vitale lost his temper and picked up a tree branch from the floor of the pine forest and struck the horse on the side of the head.

Now, the eyesight of horses is designed for grazing and looking out for danger at the same time, but horses adjust their range of vision by lowering and raising their head. They are also a little colourblind. In the pine forest, the Percheron could see the green of the trees but not the browns and greys of the carpet of pine needles, could see the blue of the sky but not the white of the clouds. In what is therefore a landscape resembling a drab mosaic, objects that are motionless convey very little information to a horse. Nor can horses see things nearer than three feet directly in front of them without moving their heads.

The Percheron did not see the blow coming, although the man was quite close to him.

Who knows what it was? Maybe his mind was churning over the bad luck, the government officials, their questions, the war. Perhaps it was his true secret nature, tired of being buried under the gentleness and kindness that was his trademark, that for once in his life ripped its way out of his guts and into the freedom at last of the warm June air.

The horse quickly reared up and away from the blow, tossed his head and screamed, pawed at the ground. The scream of a horse may sometimes be referred to as a whinny or a neigh, but these words may disguise the horror a horse can feel. A horse can indeed scream, and it is a horrible thing to hear.

Hidden in the screams was a frantic wish for the pain to stop and a prayer that it would go away, and panic at a world that had turned upside down in an instant. The man was a stranger suddenly and a monster.

The eyeball had popped out of its socket and was split. The horse was blind in one eye.

Vitale pulled hard and held the leather reins tight to prevent the horse from bolting. He struggled with his friend the horse and spoke to him reassuringly. He was finally acknowledging the horse’s presence. He hid his disgust at his own violence as well as he could. When the horse had calmed down and was crying in silence and Vitale was exhausted, not only physically but also in his emotions, and barely keeping a grip on the reins, he removed his shirt and wrapped it around the horse’s head and over the frightening eye. He took water from the drinking bucket and soaked the improvised bandage, hoping the cool would soothe the pain.

With the horse’s screams, some of the other men came running. Vitale understood the enormity of what he had done. He told the boss that the horse had walked into a low-hanging branch and had poked his eye out and that he had done his best to calm him down. See how he had bandaged the head? The gentle man accompanied the Percheron back to the camp in silence, one hand stroking the thick, powerful neck.

The precise details of the Percheron’s fate after this are not known, as Vitale did not remain with the Madera Canyon Pine Company much longer. Soon after, he left the logging camp and continued working in the vineyards around Fresno, where after several rich grape harvests he made his fortune and returned to San Ginese.

I was a small boy when my father, Vitale, told me this story, and I cried all night at the thought of the large, innocent, blind horse. My father later added a brief epilogue, which was that the horse continued to work with one good eye. When I became a man and reflected on this I wondered whether the addition to the story was true or whether my father had made it up. I also wondered why my father would tell me the story of the Percheron, and decided that it was because the truth is sometimes necessary, especially to a gentle man seeking absolution.

After I had been in Australia for sixty years and my father was long dead, I myself having reached the age at which he died, the time came when all that was left for me was to reflect on certain events in my life. It was then that I understood why sometimes at night, in the silence of the old house, my father, Vitale, the gentle man who lived to be eighty-nine and whom everybody in San Ginese loved, remembered the Percheron and wept.

Share this post

About the author

Moreno Giovannoni is the author of the critically acclaimed The Fireflies of Autumn and a freelance translator of long standing. His essay 'The Percheron' was published in Southerly and selected for The Best Australian Essays in 2014. He was recipient of the prestigious Deborah Cass Prize in 2016.

More about Moreno Giovannoni