News

News >

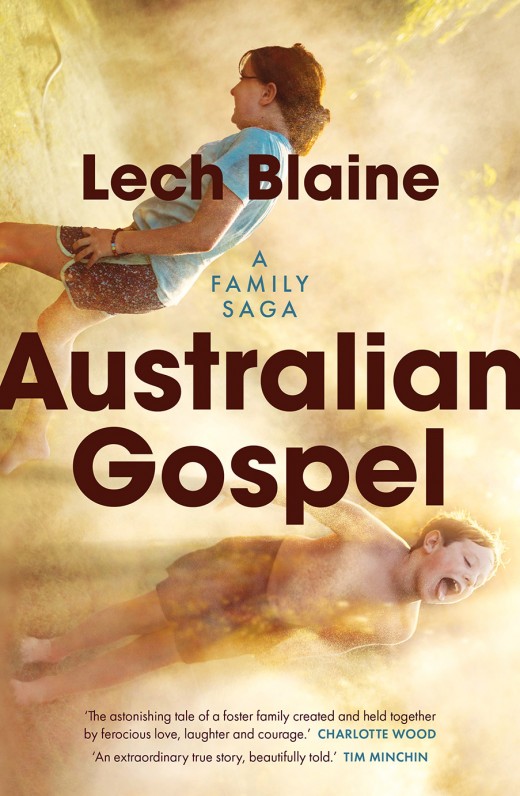

A Q&A with Lech Blaine, author of Australian Gospel

In this funny and fascinating interview, Lech tells us a bit about his family, his writing process – which partly involves sitting naked on a recliner – his favourite books and authors, and what compelled him to write Australian Gospel.

Australian Gospel is deeply personal, and it’s clear, after reading it, why you were so compelled to write it. But why was now the time to tell this story? What made you decide to finally sit down and write it?

My father died in 2011. Two years later, my mother was diagnosed with a terminal illness. I was twenty-one. It was my job to sell the house and organise a nursing home placement. Mum kept a meticulous archive of diaries, letters, newspaper articles, foster care files, court transcripts, and restraining orders.

It was a record of her marriage to my father, and their experiences as foster carers. Particularly the cases of my foster siblings: Steven, John and Hannah. They were the biological children of Michael and Mary Shelley. The Shelleys were Christian fanatics, who stalked my family and many other targets. “I’m going to write a book about the Shelley Gang one day,” my mother used to say.

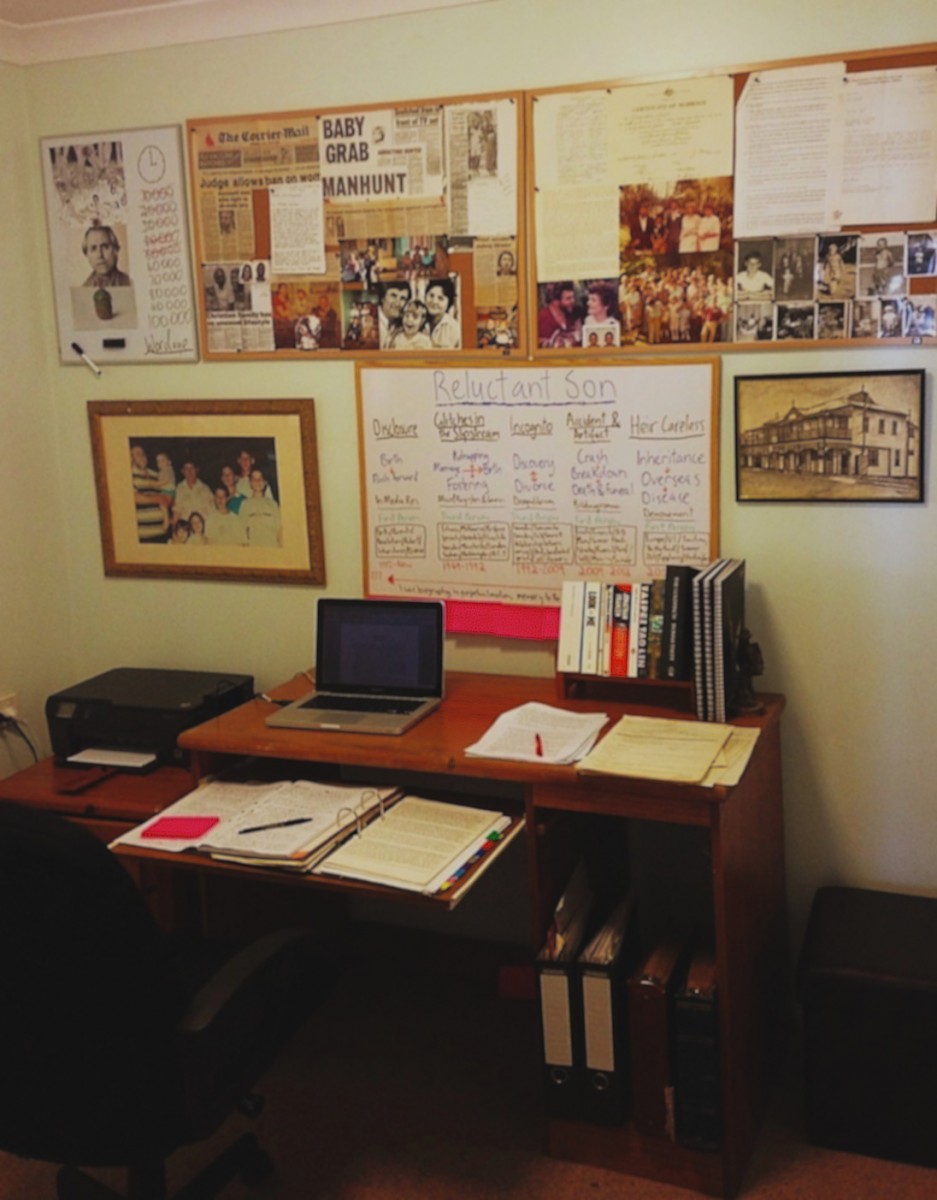

Due to illness, she never got the chance. So, I decided to write it for her. In 2013, I set up an office in the granny flat and began researching the book that became Australian Gospel. It took eleven years to finish. Running a motel and other writing projects got in the way. This was a blessing in disguise. I had no idea how many people had been affected. I needed time to find them. I also needed time to write the book from a place of curiosity and love; not fear, anger, or grief.

Lech Blaine’s writing space

(Image courtesy of Lech Blaine, 2013)

Can you tell us a little about your writing process? What sort of research material did you collect for this book, and how did you manage to transform it into a cohesive narrative?

Ideally, I wake up around 9 am, hit the button on my coffee machine for a double espresso, and sit – as soon as humanly possible – on a one-person recliner in the nude. I write for five or six hours. Then I try to go for a run. I come home, stretch, shower, and tinker with what I’ve written. Maybe make some calls if there are people I can speak to about the section I am currently working on. I don’t have a TV, or many hobbies. The night is for reading and dreaming.

This was essentially my daily routine for Australian Gospel. It was a boon for productivity, although friends questioned my sanity. For me, the most enjoyable part of writing is repetition, and the flow state while composing prose. I relied heavily on two primary sources: my mother, and Michael Shelley. Over the years, hundreds of other people came out of the woodwork, and filled in the gaps. The manuscript blew out to 200,000 words. Then I stripped it back to the core story.

If we consider Australian Gospel a memoir, then it’s your second – your first, Car Crash, came out in 2021. Do you think writing Car Crash primed you for Australian Gospel? Did it feel very different writing this book than the last one?

I don’t tend to think of Australian Gospel as a conventional memoir, à la Car Crash, though that’s still probably the easiest genre to categorise it. I’m not the main character. But the writing and editing process for Car Crash was an invaluable apprenticeship for this project. It made me a lot less precious on a sentence level.

This was a way more enjoyable experience. I tried to let the words and actions of the characters do the heavy lifting. If I had written Australian Gospel first, I think it would have been less succinct and funny; more ornate and theatrical. Because I hadn’t learned to trust the reader to make sense of the material themselves.

What are some of your favourite books, and who are some of your favourite writers? How have these informed or otherwise influenced your writing style and, more specifically, the writing of Australian Gospel?

My favourite book of all time is Underworld by Don DeLillo. In my late teens, I was obsessed with his novels, and the cadences of his sentences. It took a while to find my own style, and to realise DeLillo’s use of irony didn’t necessarily suit the stories I wanted to tell. Australian literature helped me believe my own voice. I’ve frothed Helen Garner, Tim Winton and Christos Tsiolkas for a long time.

I also reckon that Australia has some of the best narrative non-fiction writers in the world, such as Chloe Hooper, Anna Funder, Sarah Krasnostein, etc. While working on Australian Gospel, I read a lot of family sagas. The title is a nod to one of my favourite novels: American Pastoral by Philip Roth. Pachinko by Min Chin Lee was an inspiration. Both its wide social scope, and the brevity of the prose.

Did you always want to be a writer? What would you be doing if you weren’t writing?

I always thought of myself as a writer, before I knew that this was a legitimate occupation. Mum passed on a love of reading and writing. I also had political aspirations as a kid. Thanks to therapy, I realised this was fuelled by a messiah complex. I went from being 100% convinced I was right about everything, to being 99% unsure. A great trait for a writer, but not a politician. I have no idea what I would do if I wasn’t writing. It’s a personal compulsion that just happens to be providing a career for the moment. I’m too neurotic for an office job.

Having now written two incredible memoirs, what sort of book might be in store for you next? Any works in progress, ideas, desires?

The jury is out! I’ve always wanted to write a novel, but I haven’t had a chance to flex my fiction muscles since I started Car Crash and Australian Gospel. I’m blessed with material from my years running a 3-star motel in Bundaberg. Time will tell if I use fiction or non-fiction to depict that singularly insane experience.

Share this post

About the author

Lech Blaine is the author of the memoir Car Crash and the Quarterly Essays Top Blokes and Bad Cop. He is the 2023 Charles Perkins Centre writer in residence. His writing has appeared in Good Weekend, Griffith Review, The Guardian and The Monthly. His latest book is Australian Gospel.

More about Lech Blaine