News

News >

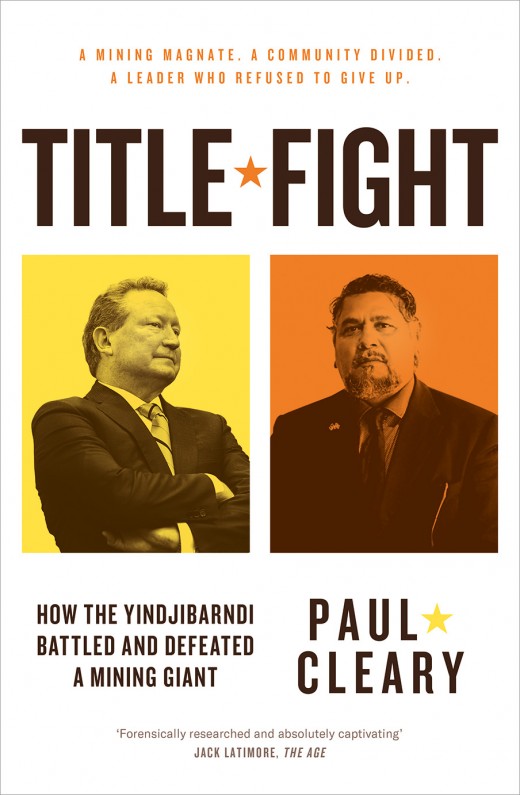

A Q&A with Paul Cleary on the Yindjibarndi community and Fortescue Metals Group dispute

As the Federal Court case between the Yindjibarndi community of the Pilbara region and the Fortescue mining operation continues, Title Fight author Paul Cleary has you covered for the past, present and possible outcomes of the conflict.

You wrote a whole book about it, so there's a lot to say, but can you give a quick summary of the conflict?

Title Fight is about a David and Goliath battle between the Yindjibarndi community from the Pilbara region and Fortescue (FMG), the company controlled by Australia’s richest man Andrew Forrest. The Yindjibarndi people have secured the strongest form of native title rights over the land where FMG has built the gigantic Solomon hub mine, which has earned $US50bn in revenue since 2013, but FMG hasn’t paid a cent in compensation and has destroyed around 250 heritage sites, such as rock shelters, and severely impacted others that remain.

What is happening in the case now?

Because FMG went ahead and mined without the consent of the Yindjibarndi people, the community has initiated a compensation case in the Federal Court. Justice Stephen Burley heard evidence over nine days in August, with five of those held in a PCYC hall in the town of Roebourne, and four in a makeshift bush court set up in a sacred place called Bankangarra.

Some of Justice Burley’s comments and questions were quite telling. At one point, he said that if miners can act in the way that FMG has done, then it makes native title ‘irrelevant’. A report by Daniel Mercer from the ABC said that the case ‘cuts to the heart of Australia’s native title rights’.

What’s at stake for both parties? And are there wider implications for the mining industry and other First Nations groups?

The implications are huge, and this case is shaping up the biggest test case for native title rights since the Mabo case, which went before the High Court in 1993 and then led to the Native Title Act. If Justice Burley sides with the Yindjibarndi community, it should mean that miners can no longer ignore the rights of Aboriginal communities whose rights to land have been affirmed by Australia’s justice system.

Why has the federal court set up in the Pilbara? Is that common practice?

I believe that this is the first time the Court set up in a bush setting for a damages claim, whereas it has done so for native title cases. The Federal Court did an amazing job of running these hearings and live streaming the evidence. As part of the hearings, the Court went on a mine site visit that lasted an entire day and at various places people gave evidence about the cultural heritage that remains, and those sites that have been destroyed. It was a very emotional day for the community as they saw the vast scale and impact of the mine. People were crying. The chair of the Yindjibarndi corporation, Stanley Warrie was in tears when he cried out about his land being ‘stolen’ and ‘destroyed’. He said: ‘This is my religion, and it’s been destroyed, my stories, my life.’

How do you think things will turn out?

It is really hard to predict as this case has taken native title into uncharted territory. One thing for sure is that everyone accepts that the Yindjibarndi people are entitled to compensation. FMG said it should be paid by the State, and the State government’s counsel said that FMG was liable. A new element in this case, which has never been tested before, is the social disharmony fomented by FMG as it sought to divide the Yindjibarndi community by creating a breakaway group that supported the development. There is a section of the WA mining act that says communities can be compensated for social dislocation, so the Yindjibarndi counsel is seeking compensation under this section, as well as the economic, cultural and spiritual damage caused by the mine.

It is hard to see that the judgement will condone FMG’s behaviour in any way, and I think it’s quite likely that it will condemn this rogue and insensitive behaviour. It is incredible that just eight days after the mine site visit, FMG staged its twentieth anniversary ‘party’ at the Solomon mine, with many of the guests oblivious to, or not really caring about, the native title rights of the Yindjibarndi people over the land where the Solomon mine has been built, and that the mining has wrought great devastation to this land and emotional damage to the community.

To learn more about Paul Cleary’s book Title Fight and to read a chapter, click here.

Share this post

About the author

Paul Cleary began his career with Fairfax, leading to a decade of economic policy reporting in the Canberra press gallery. After studying in the UK as a Chevening Scholar, he became an adviser to Timor-Leste on resource negotiations. His work has focused on resource conflicts and policy, and his books include Trillion Dollar Baby, Mine-Field, Shakedown and Too Much Luck, which The New Yorker described as a ‘fierce, concise book’ that investigated how the resources …

More about Paul Cleary