News

News >

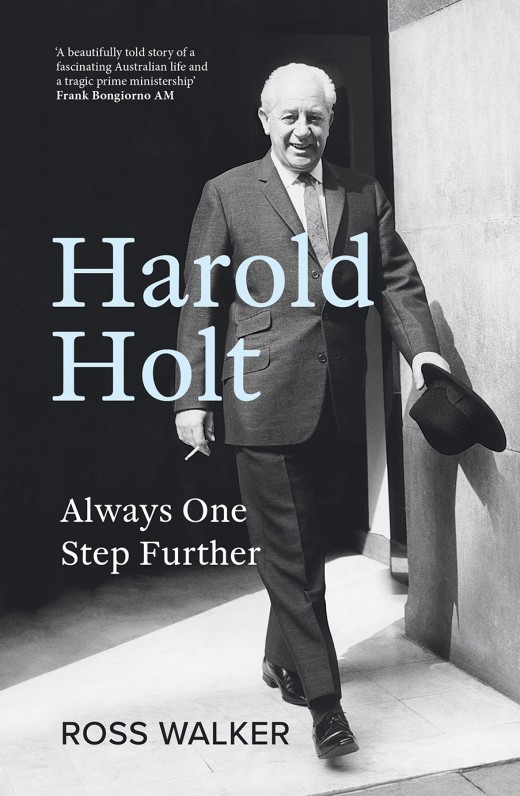

Read an extract: Harold Holt

A revelatory biography of Harold Holt, the prime minister who helped create modern Australia. Read an extract.

If ever I am banished, I am going to Australia.

—Lyndon B. Johnson, quoted in The Age, 17 October 1966

It was like watching a move in which the first appearance of the star is delayed to heighten the suspense. In the lead up to Thursday 20 October, Australian newspapers continually headlined the impending arrival of President Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife, Lady Bird. The president had accepted Holt’s invitation and would be the first serving American president ever to visit Australia; he would be the most important American visitor since Douglas MacArthur in 1942. After his four days in Australia, he would go to Manila for a conference of the Vietnam allies.

The president’s youthful press secretary, fellow Texan Bill Moyers, reached Australia ten days early to prepare the logistics of the visit and to brief the press. He had been by Johnson’s side since he was eighteen, when he applied for a job with then Senator Johnson. After starting by addressing envelopes, he was promoted to answering letters from the senator’s constituents. When he heard the news that Kennedy had been assassinated, he went straight from Austin to Dallas, to the plane on which Johnson was being sworn in as the new president. He had a note for him: ‘I’m here if you need me.’

Johnson did need him. Sometimes he thought of him as the son he did not have. There was no Lyndon Baines Johnson Junior, but there was Billy Don Moyers, the former divinity school student and Baptist pastor, looking studious in his black-rimmed glasses, impeccably groomed, his boss’s idea of what a young American man should be. Their connection was so close that Moyers said they were joined by an umbilical cord, suggesting that Johnson was a mother as well as a father to him. But Moyers managed, when necessary, to resist the pull of Johnson’s often overpowering world. ‘I work for him despite his faults,’ he explained, ‘and he lets me work for him despite my deficiencies.’

He had the reputation of being the only man who could say ‘no’ to the president or put him in his place, such as when he was saying grace before a meal and the president demanded that he ‘speak up’ – ‘I wasn’t addressing you, Mr President,’ he replied. Moyers had recently been troubled by the war in Vietnam, and this was becoming a source of tension between the two men. At last the moment came when the Johnsons arrived on Australian soil. ‘They’re really here,’ the prime minister excitedly told his wife. Johnson was ‘the biggest fish I ever caught’.

A rainbow was arching across the darkening sky as the president stepped out of his plane and strode towards Holt and the rest of the reception committee. He knew he would get a better reception in Australia than almost anywhere in his own country. Two years earlier, he had barnstormed the country campaigning for re-election, greeted everywhere by enthusiastic crowds.

Since then, as the war in Vietnam intensified, his popularity had slumped. Mid-term elections were approaching in America, but he decided to leave the campaigning to others and instead play the statesman overseas. On the other side of the world, he could be of some help to his friend Holt, who had his own election to win. To Australians, Johnson held an office that still retained some residual glamour from the Kennedy years, and, like MacArthur, the president was coming in a time of war, the iron chain that linked America with Australia.

He reframed Holt’s promise to be ‘all the way with LBJ’ so as to make it sound more temperate:

When your prime minister symbolically said in Washington, in speaking of the crisis that faced our men on a faraway battlefront at the moment, that he would go all the way with LBJ, there wasn’t a single American that felt that was new information.

But Holt continued to repeat this slogan, a mantra that seemed to make him feel more secure. It was as if he had conflated his sense of his own security with Australia’s.

The next day at Parliament House, Johnson spoke at a luncheon held in his honour; Holt listened with head bowed deferentially. Every so often he applauded, politely but enthusiastically, especially when the president, smacking his huge hands together after every major phrase, declared that,

There’s not a boy that wears the uniform yonder today who hasn’t always known that when freedom is at stake, and when honourable men stand in battle shoulder to shoulder, that Australians will go all the way, as Americans will go all the way, not part of the way, not three-fourths of the way, but all the way, until liberty and freedom have won.

Calwell, by contrast, was less deferential. Johnson was moved by Calwell’s words expressing affection for the United States, but visibly annoyed by his claim that there was no real difference between the Democrats and the Republicans. The two parties, he said, were like ‘empty bottles with different labels’.

For Johnson, this was a sentimental return to Australia that reminded him of a simpler time during a war that attracted almost universal support. He planned to revisit the people and places that remained in his affections, such as Melbourne and Norman and Mabel Brookes, and Townsville and Buchanans Hotel.

Later that afternoon, his first motorcade took him along Swanston Street in the middle of Melbourne’s central business district. He pointed to the man sitting beside him in the car and shouted to the crowd: ‘Here’s your prime minister!’

Holt, for his part, looked happy, a man who had finally come home to himself and to his place in the wider world. He had initiated this visit and was shining in reflected light. Even the Melbourne Town Hall seemed to acknowledge Johnson’s presence, for behind him was the foundation stone that had been laid on the very day of his birth – 27 August 1908 – as if his influence had impregnated the building itself. That was also the birthday of Sir Donald Bradman, one of Australia’s most revered sportsmen. But today belonged to Johnson, as he shouted through his megaphone, ‘Australia, I love ya!’

The president then made a visit to see Norman and Mabel Brookes at Elm Tree House, their South Yarra home which had been extensively remodelled since Johnson’s visit in 1942. The Johnsons, Holts and Brookes posed for the cameras, the prime minister smiling unselfconsciously. Dame Mabel was arrayed in satin and pearls. Lady Bird Johnson, in a bright red suit, with Norman Brookes’ hand around her right arm, smiled straight into the camera.

A gathering crowd outside raised a roar to bring out Johnson, which the president could not resist. With them went Rufus Youngblood, the bodyguard who had shielded him with his own body on the day of Kennedy’s assassination, and who had become a fixture by the president’s side.

The crowd was in awe of Johnson. ‘Touch my baby!’ screamed one woman, dragging the child from its pram and holding it over four or five rows of heads. Johnson’s long arm flashed out and patted the infant.

Two brothers, aged eighteen and twenty-one, came with a different purpose. Johnson was already inside his car when he saw the paint spatter it, along with four bodyguards and some bystanders, with the red and green colours of the Viet Cong.

By the next day, LBJ was in Sydney. The tickertape fell like confetti, as if to bless the union between the United States and Australia. But demonstrators were waiting with signs as the presidential party reached the National Gallery of New South Wales for a reception. ‘CONSCRIPTION MEANS VIETNAM’ read one placard, with the ‘T’ in Vietnam represented by a series of crosses, spreading ever outwards into an unending toll of death.

Despite these blemishes, the visit was a success. Together, Holt and Johnson visited Queensland, then flew on to Manila. Johnson must have been thoroughly talked out following his trip to the Antipodes and Asia, for shortly after his return to Washington he had to be hospitalised for the removal of a polyp on his vocal chords. Holt rang him to wish him well for the operation, which Johnson received warmly: ‘Glad to hear you . . . We have most pleasant memories of our visit there and I got some nice pictures I’m gonna send you. You look like a movie star.’ Holt reported that his grandson had become a new admirer of Johnson’s: ‘Young Christopher’s got your picture hanging up now in the bedroom. It’s an inspiration to him.’

The president chuckled at this news. But he would have to rest his vocal cords for a while after the operation. Lady Bird had never known him to be speechless before, and promised that ‘we are going to make the most of it’.

Share this post

About the author

Ross Walker was for many years a high-school teacher of English and English Literature, about which he has published several books and many articles. He has a doctorate in American literature, and specialised knowledge of Australian and American politics, especially during the 1960s.

More about Ross Walker