News

News > Extract

Read an extract: My Tongue Is My Own

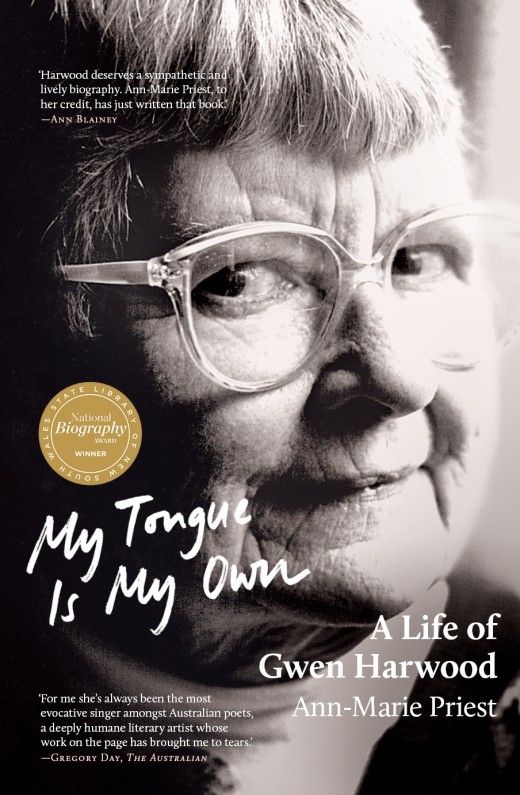

The first biography of Gwen Harwood (1920–1995), one of Australia’s most significant and distinctive poets. Read an extract.

Gwen Harwood took great interest in the writing of her biography. In general, she was wary of literary scholars; having people pontificate about her in print made her feel like ‘peaches being put in a tin & the lid soldered on’. But when it seemed, in the early 1990s, that more than one biographer had taken on the task of writing her life story, she was pleased. With two different versions of her life in circulation, she might slip between them. There would be room to manoeuvre, a suggestive in-between space for her to occupy. For a time, she encouraged both would-be biographers to believe that he or she alone was her ‘official’ choice, sending them off to hunt down her letters and speak to old friends. In her mind, the book to be written by her long-time friend and Harwood scholar Alison Hoddinott would be a ‘sensitive’ literary biography, while the one by young medievalist Gregory Kratzmann would ‘dish the dirt’. The would-be biographers found the situation less than ideal, however. When Hoddinott discovered that Harwood had made the same promises to them both, she withdrew, leaving Kratzmann in possession of the field.

Over the following months, as the friendship between Kratzmann and Harwood grew, the poet became less and less guarded, giving him access to restricted papers held in various library collections and telling him things she had never told anyone else. She wanted to be known, to share her secrets. She was very curious about how he would tell her life story, and even suggested some possible opening paragraphs for his use. In one, she impersonated her biographer coming upon his subject unawares:

Before I opened the door of All Saints I heard the swelling harmonies of a Bach prelude, brilliantly played; inside, as my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I became aware of the diminutive, surprisingly youthful figure of the organist, engrossed in her playing. Could this be the author of ‘Burning Sappho’ and ‘Carnal Knowledge’? I asked myself ...

Another made shameless use of the opening line of David Marr’s biography of Patrick White, which she had recently read: ‘The bride was a pretty woman who did not wear a big hat. A big hat would have obscured her face ...’

Yet another introduced a sinister twist: ‘Long ago a titian-haired girl child was born in a nursing home at Taringa to a couple called Joe and Agnes. They called her Gwendoline Nessie, “Gwendoline” for a friend of her mother, “Nessie” for her mother. Nessie, of course, is also the name of a monster ...’

Needless to say, none of these openings was ever used. Harwood died before Kratzmann was far into his book, and with her husband and other key people still alive, the project became too difficult to navigate. Kratzmann decided to publish a volume of her letters instead – a glimpse of her life, as he thought of it, in her own, genuinely inimitable words.

This compromise would have pleased her. She was the trickster-poet, after all, the enigmatic woman of many masks and numerous voices. Even as a young woman, she hated being confined to a single identity, a single narrative, a single voice. At twenty-two, working as a clerk in the public service in Brisbane and playing the organ at weddings on weekends, she liked to channel a range of artistic personas. ‘I have three characters – with variations – which I play at weddings,’ she told a friend: ‘the Young Genius, the Soulful Maiden and the Embittered and Disillusioned Musician. Circumstances and singers determine which I am to be.’ These characters were parodies, but they were also dimensions of herself that were highly satisfying to perform. A little less than two decades later came the first of the pseudonyms with which she would launch guerrilla raids on the Australian literary establishment. The earnest Walter Lehmann was the author of a pair of acrostic sonnets smuggled into The Bulletin – one of which read ‘Fuck all Editors’ – that brought the Vice Squad down on the august journal. Even as all hell broke loose, the anguished Francis Geyer, a supposed migrant-musician from Hungary, continued to sing to his lost love on The Bulletin’s famous Red Page. Most daring of all was the ‘lovely lady poet’ Miriam Stone, who wrote a series of furious, brilliant poems about domestic life. In this disguise (‘Nobody will be expecting me to be a lady poet’), Harwood was able to say things about women’s experiences that nobody else was – until she was outed by eagle-eyed readers and had to shut Mrs Stone down. The Australian poetry community was in a frenzy. ‘It was not simply that a new and unsuspected poet of virtuoso technical accomplishment, wit and insight had appeared,’ wrote poet Andrew Taylor. ‘Rather, there seemed to be two of them, or possibly more. Guessing which poems, over different names, in The Bulletin were actually written by Gwen Harwood became a regular game.’

In her private life, Harwood was always alert for crossovers between the everyday and the storied realm. As a 1950s housewife, she was ‘the stately flower of female fortitude’, endlessly capable and good-humoured. As an aspiring poet, she was Burning Sappho, a woman of incandescent gifts, cruelly caged in Hobart suburbia and fighting for her life. Neither role contained her. ‘I wish I had several lives,’ she once sighed, ‘one for songs, one for poetry, one for being an abandoned alcoholic, one for being a cored and peeled hausfrau, one for beachcombing, one for being an Italian ...’. In her seventies, she told an audience at a poetry reading that she had been born in the back streets of Naples and left on a doorstep in a wicker basket with ‘a bag of sweet biscuits and a packet of dry spaghetti’. Fortunately, she had been adopted by an Australian couple who were touring Italy – which was why her maiden name was Foster. (Her friend Chris Wallace-Crabbe, who shared the stage with her that day, said it took a few moments for the audience to realise that this story was entirely untrue. He wondered if it might have been inspired by Peter Sarstedt’s ‘Where Do You Go To, My Lovely’ – a song Harwood certainly knew.)

Harwood’s great imaginative fecundity when it came to the stories of her life was partly sheer exuberance; her inventiveness bubbled up like a spring, set off by anything at all. But it was also a form of resistance to being corralled into fixed roles and identities. When I began, tentatively, to follow in Hoddinott’s and Kratzmann’s footsteps, trekking around the country to visit the various repositories of Harwood’s letters and papers, I was dazzled by the playful brilliance of her personal writings. Her letters – of which there are several thousand, many still unpublished – made me laugh aloud. But for all her merry wit, it was evident that she often felt painfully trapped. Her letters to her closest friends – Ann Jennings, Edwin Tanner and, later, Alison Hoddinott – speak of her restlessness, her impatience, her resentment of a confinement from which she could never quite break free. Long before second-wave feminism hit Australia in the early 1970s, she was aware of the ways in which women’s lives and potential were constrained by social ideals of womanliness. Yet as a young woman, she herself had succumbed to the ideal of ‘Holy Motherhood’, making earnest efforts to mould herself into the shape she believed she should take, one that would please her husband, society and her own demanding self.

She would later date this torturous period precisely: it began with her marriage and continued for twelve years. This was also, not coincidentally, the period of her poetry apprenticeship, when she was reading widely and trying on different voices, approaches, techniques and subjects. Yet in all this time, she rarely wrote of herself, from herself. It was only when she began to realise the deforming effects of her efforts ‘to please others who were indifferent’ that she began to give attention to what she would later call ‘the self that made my tongue my own’. This was the self – not single, not simple – whose contradictory and multiplicitous impulses, fed by music and literature and sex and friendship and her own fierce intellect, created all the characters and roles, all the loves and hates, all the interweaving voices of her poems. ‘No-one may like the shape I take,’ she growled in the 1970s, ‘but no-one is going to espalier me again.’ When she claimed the right to find her own shape, she became that rare poet who forges her own distinct style. With her fierce ‘independence of spirit’, she discovered the gift of communicating her inner life to her readers – thus making her way into theirs. She went on to become the poet Peter Porter would describe as a ‘true master’, the most accomplished Australian poet of her century.

*

This is not to say that Harwood made a straightforward progression from silence to a confident, assured poetic voice. To read her letters, memoirs, stories and poems together is to understand the assertion she once made that she was ‘full of old selves, half-devils inhabiting the body’. There was no clean break, no simple rebirth. Indeed, her determination to achieve some ‘independence of spirit’ caused her pain and trouble, and often deep unhappiness. It brought her into conflict with those she loved, and with herself. More than once, after vowing to never again allow herself to be trellised, she would catch herself busily pruning her new growth into the old shapes. Yet, however imperfectly it was realised, her determination persisted.

While she was still young, she found a story that resonated with her efforts at self-liberation. In its earliest incarnation, ‘Thomas the Rhymer’ was a seventeenth-century English ballad, but Harwood also knew it as a German poem set to music by Carl Loewe. True Thomas is a wandering poet who is taking his ease by the river one day when a fair-haired woman rides up – the most beautiful woman he’s ever seen. She tells him she is Queen of Elfland, and warns him that if he once kisses her, he will belong to her for seven years. Dazzled, slain, Tom takes her in his arms. Seven years of servitude, he tells her, is a small price to pay for such a prize. He kisses her, she kisses him, and she takes him up on her milk-white steed and rides with him to Elfland. ‘How happy the Rhymer was,’ carols Loewe’s lied.

The German song ends there, but the English ballad continues for many more stanzas. When the queen and the Rhymer come at last to the border of Elfland, she reveals a caveat she had not mentioned before: while he is in her kingdom, he must not speak. No matter what he sees or hears, he must stay silent. If he says a single word, he will never return to his own land. As she tells him this, she plucks an apple from a tree and gives it to him as his reward. It is a magic apple, and when he returns to his own country it will give him a ‘tongue that can never lie’. Far from being grateful, Thomas is indignant. A true tongue is hardly a reward, he points out. How is he to ply his trade? ‘My tongue is my ain,’ he declares. But the elven queen is inexorable, and bids him hold his peace: ‘For as I say, so must it be.’

Harwood identified with Tom the Rhymer – particularly his spirited assertion that his tongue was his own. She believed that when she married, she willingly surrendered her voice for love, disappearing into Elfland. Unlike Tom, though, when her years of servitude were over, she was determined to ‘keep my tongue my own’. Owning her tongue was about claiming the right not only to speak but also to be silent – even to lie. It was about using her voice as she chose: to hide or to reveal herself, to try out different characters, different truths and possibilities, and to speak – as she put it in another poem, ‘Chance Meeting’ – the love she felt compelled to own. It was about claiming her sexual freedom, too. Above all, it was about.

This is an extract from My Tongue Is My Own by Ann-Marie Priest. To read more, order

My Tongue Is My Own – out now.

Share this post

About the author

Ann-Marie Priest is the author of the first biography of renowned Australian poet Gwen Harwood, My Tongue Is My Own (2022), and recipient of the 2017 Hazel Rowley Literary Fellowship. Her book A Free Flame: Australian Women Writers and Vocation in the Twentieth Century was shortlisted for the 2016 Dorothy Hewett Award. She is a senior lecturer at Central Queensland University.

More about Ann-Marie Priest