News

News >

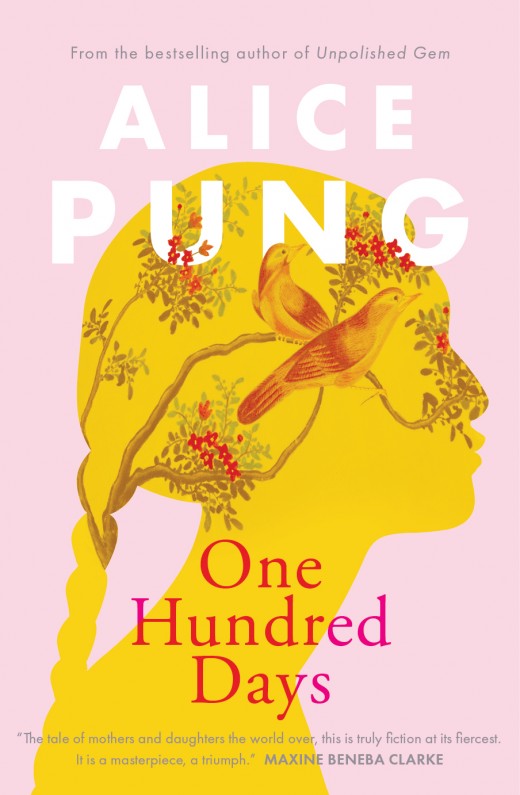

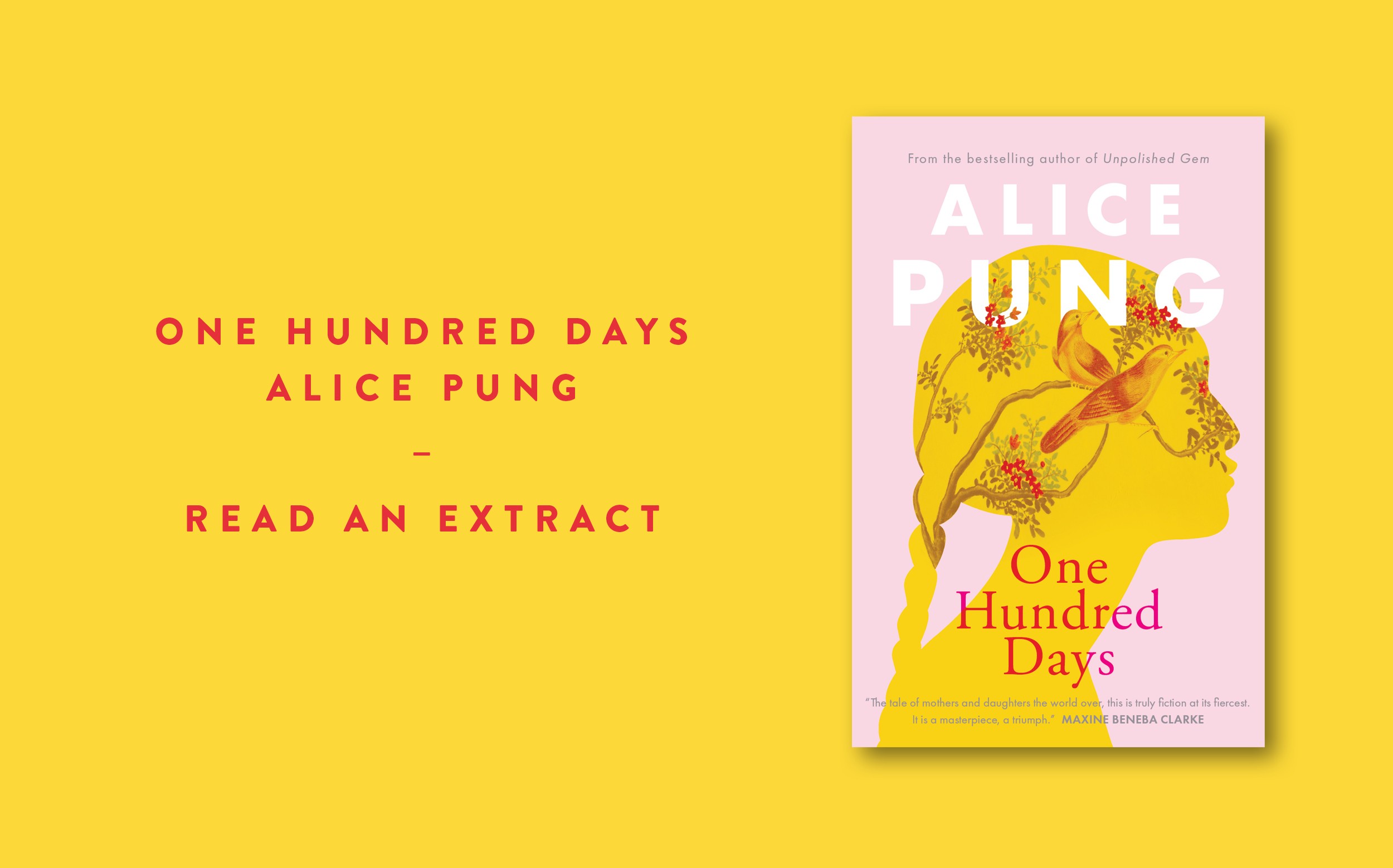

Read an extract: One Hundred Days

In a heady whirlwind of independence, lust and defiance, sixteen-year-old Karuna falls pregnant. Read an extract from One Hundred Days, the new novel from Alice Pung.

Ever since your Grand Par left, your Grand Mar and I share the double bed. She says she can’t sleep by herself, that it’s too dark, even though the hallway light shines on the stippled cement dots on our ceiling. It’s like an asphalt galaxy up there, like the road is above us instead of fourteen floors below. I hate sleeping with your Grand Mar. In the months after your Grand Par left, she used to work herself up into such a state that her chest heaved like engine pistons going up and down, up and down, like the organs inside the ribcages of the cars your Grand Par showed me. I once saw a documentary about a woman who could only breathe through iron lungs. She was part-machine, a horizontal robot that was half-deflated. That is how your Grand Mar was in those early days, a sad sack of skin bagging a mechanical-breakdown chest.

Your Grand Mar always said that if I had been a son, then he would’ve stayed. “Boys belong to their fathers, girls belong to their mothers,” she’d tell me, which would really piss me off because I didn’t want to belong to anyone.

It would be nice if I could start off with a fairytale, something that makes you think that the world is much bigger than us beneath our ceiling. But it’s just me and you and your Grand Mar and the dark, and even though I would like to begin anywhere but here, here is where I am and where you start.

In the dark there is no big bad wolf, even though your Grand Mar wants to wring his name out of me. In fairytales the princess stays silent, because if she blurts out even one syllable, snakes fall from her mouth, or the kingdom collapses, or her firstborn is doomed. As for the hero prince, well, he can say whatever he likes; worlds never crumble when he rabbits on. Sometimes the beast and the prince are the same person, but you will find these things out for yourself, I think.

I know your Grand Mar stares at me in the blackness. I can feel her head turning on her pillow, and then she asks, “Who is it?”

When I don’t answer, she says, “Do you even know who it is? Because if you don’t know who it is, we can get the police to look for them and catch them and lock them away.” She says this to me like I am five years old and don’t know about the law. “In jail,” she adds.

When I still won’t talk, she mutters, “Never knew any girl could be so dumb.”

I am not dumb, even though I know your Grand Mar thinks this every time I make a decision that has nothing to do with her. She has to say yes or no to every thought of mine, and it gets harder and harder to have secret thoughts since we share the same bed and she bugs me every night, but I have this notebook and she can’t read what I write even if she opens it (which she has) and grills me about it (which she also has). “Just practising my writing,” I tell her, which is not a lie at all, “for when I go back to school,” which we both know is a lie.

When she is not in such a dark-dark mood, she is even patient and cajoling. “You can tell your Mar,” she says. “You know I want to help you. You will not get into any trouble if you let me know.” I hate this even more than her anger. I know she will go back on her word, that I will not only get myself into trouble but your dad too.

I say nothing, and predictably, after a few seconds, she falls back into her angry state, sizzling and hissing like water on a hotplate.

“Will it be a Ghost baby or a human baby?” she spits. I say nothing.

Being so close to her makes me curl up inside myself like a cashew. Your Grand Mar wishes she could have known about you when you were the size of a nut, because then she could have found a way to shake you from your shell. But even I didn’t know about you then.

Your Grand Mar is not the only one who says I am stupid. They look at me like I’m a caged bunny that escaped and got myself into a bad state, all soft paws and silent yowls. But your father was not a criminal. He was just a boy I liked, and then he left, but by then you were here.

And like some mythical monster, I now have two heartbeats. “Listen, can you hear that, Karuna? That’s your baby’s heartbeat,” Dr Masano said, when she first put the fetoscope to my stomach. I’d waited too long to see the doctor, so the first time I heard you, you were a loud and frantic throb.

“It’s scared,” I told her. “That’s why its heart is beating so fast.” Before you’d even begun, I felt like I’d stuffed up, stuffed you full of my own fears.

She laughed. “No, don’t worry, the reason the heartbeat is so fast is because the baby’s so tiny. It’s the size of a passionfruit.” Ha, I thought, passion fruit. I remembered all those Hail Marys at Christ Our Saviour College, kneeling during confession, trying to keep a straight face at “fruit of thy womb”. When your Grand Par left, he took that faith with him as well, because that was the end of my private school education.

Now, lying in the dark with your Grand Mar next to me, depressing half the bed and all of my life, I can only wait for you to come and shake things up.

And the one hundred days have only just begun.

One Hundred Days is in bookstores now.

Share this post

About the author

Alice Pung OAM is an award-winning writer based in Melbourne. She is the bestselling author of the memoirs Unpolished Gem and Her Father’s Daughter, and the essay collection Close to Home, as well as the editor of the anthologies Growing Up Asian in Australia and My First Lesson. Her first novel, Laurinda, won the Ethel Turner Prize at the 2016 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. One …

More about Alice Pung