News

News >

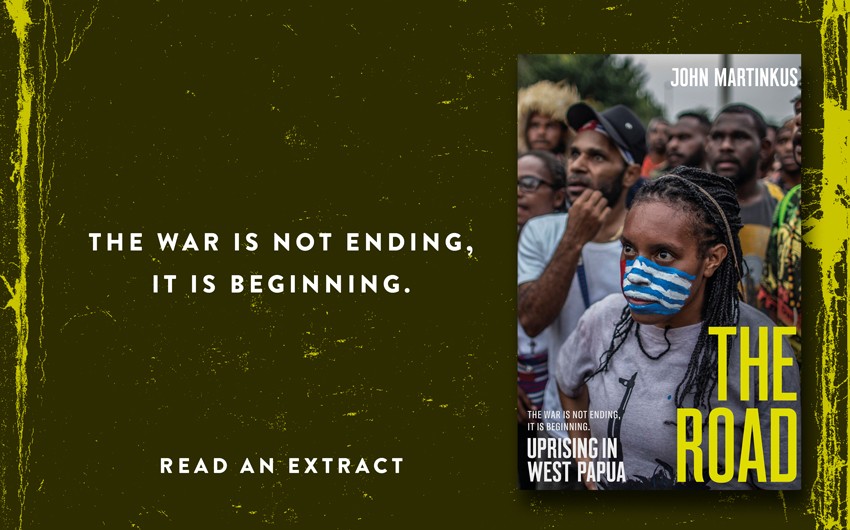

The Road: Read an extract

The story of the unfolding West Papua uprising told by acclaimed journalist and foreign correspondent, John Martinkus.

This is a story that covers many years and many trips I made to far-flung parts of Indonesia, mostly in search of conflicts to report on. I wanted to go where no Western journalists were allowed. I started in the mid-1990s in East Timor, now the independent country of Timor Leste, travelling as a tourist because journalists were banned. I hung out there, despite regular casual death threats and constant surveillance. Eventually I got up into the mountains with the pro-independence guerrillas. I hiked quietly with them in the jungle and slept in a tarpaulin-covered hole with branches over the top, hiding from the Indonesian troops who came so close we could hear their boots breaking twigs in the scrub. That band of men were mostly killed or captured the following year, after they attacked and killed thirty Indonesian police in an ambush near their hideout. Their commander, David Alex, was taken alive but never seen again.

I returned to East Timor again and again and, following the fall of the dictator Suharto in May 1998, I was able to stay there permanently and obtain a journalist visa. I covered the rise of the student opposition, reporting on the marches and protests and the inevitable backlash by the Indonesian military and the militias they used as a screen to hide their killing. Weeks that turned into months were spent covering massacres and killings across the provinces. Counting bodies, getting numbers of the dead. Basic reporting, really, but always in the face of threats from the Indonesian military, the police, their intelligence operatives and their militias, as they maintained the fiction that they were simply trying to keep the peace between two warring Timorese sides: the pro-independence movement and the Timorese militia, whom they were arming, organising, paying and driving around, and sometimes impersonating, to massacre their fellow citizens. For the record, Australia went along with this fiction until the final days, when the Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence and the Indonesian state turned on both the East Timorese – killing those they deemed pro-independence, burning and depopulating their towns and villages – and the foreign community, forcing them to evacuate so they could finish their job without foreign witnesses. It is a modus operandi the Indonesian military used again in Aceh in 2003 and, at the time of writing, is using in West Papua.

During Indonesia’s reluctant and destructive and brutal withdrawal from East Timor following the arrival of the Australian-led peace-keeping force, we journalists continued to report on the violence. We travelled to neighbouring West Timor to document the almost one-third of the East Timorese population who had been forcibly evacuated there, driving past the piles of looted televisions, motorbikes, furniture, even electrical wire torn from power poles that rotted in the monsoonal rain just over the border. Then there were the camps – thousands of desperate people being held by the ‘militias’ as a kind of bargaining chip. Over the next six months, most of them were eventually repatriated to East Timor, but not before many had been raped or killed. In the capital, Kupang, I went to the old expat bar on the waterfront. Teddy’s had always been a seedy place full of Australian men drinking in the morning and eyeing off the bored-looking girls. This time there was no one there but myself and a drunk East Timorese soldier from one of the notorious 744 and 745 Battalions, made up of East Timorese with Indonesian officers. They had just killed nuns, a priest, two journalists and many, many civilians as they made their way out of East Timor. He asked me to buy him a drink and rolled a grenade across the bar. I bought the drink, downed mine fast and left.

Ironically, out of this chaos and uncertainty there followed a period of roughly four years when journalists were able to take advantage of a relative freedom in Indonesia. We could visit Aceh, at the far north-western tip of Indonesia, and Papua, in the far south-east, where separatist wars had simmered ever since the territories had been integrated into the Indonesian nation. Both areas had long been banned or heavily restricted to foreign journalists. Entering these regions was difficult and intimidating, with constant document checks, threats of violence and the ever-present surveillance by the Indonesian intelligence services, but it was, for the first time, possible. That is how, as most of my colleagues went to Afghanistan when war broke out in 2001, I ended up in Aceh. And how, when war was mounting in Iraq in 2003, most of my colleagues went there and I ended up in Merauke, Papua. The south-easternmost town in Indonesia. Literally the end of the road.

The Road is published Monday 18 May. Pre-order now.

Share this post

About the author

John Martinkus is a four-time Walkley Award–nominated investigative reporter on the Asia and Middle East regions. His eyewitness account of East Timor’s struggle for independence, A Dirty Little War, was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards. His books include Travels in American Iraq, Indonesia's Secret War in Aceh, the Quarterly Essay Paradise Betrayed: West Papua’s Struggle for Independence and, most recently, The Road: Uprising in …

More about John Martinkus