News

News > Book Launch

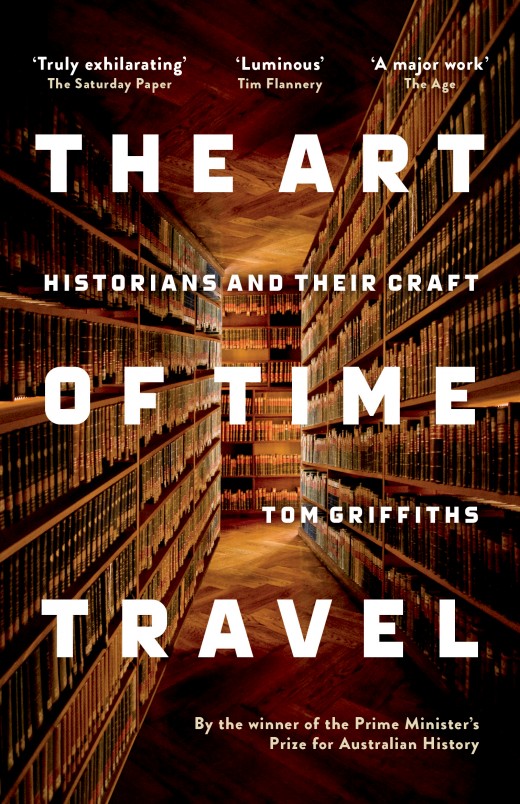

Frank Bongiorno on The Art of Time Travel by Tom Griffiths

Tom Griffiths new, landmark work The Art of Time Travel explores the craft of discipline and imagination that is history and received glowing praise on release last month. The Australian called it ‘a manifesto for a new understanding of Australia’ and the Monthly recommended that it ‘should be in every school and library’.

In his launch speech at The Australian National University, Frank Bongiorno offered his own thoughts on why the books is such a special one: ‘The Art of Time Travel will explain to such readers better than any other book I know what it is that historians do, and why what they do should matter to everyone.’ Read his speech in full below.

On the second page of The Art of Time Travel, Tom grapples with the historian’s mission. He writes:

Historians tend to be dedicated, passionate citizens who seek to make a difference by telling true stories. They scour their own societies for vestiges of past worlds, for cracks and fissures in the pavement of the present, and for the shimmers and hauntings of history in everyday action. They begin their enquiries in a deeply felt present. But as time travellers they have to forsake their own world for a period – and then, somehow, find their way back.

‘To make a difference by telling true stories.’ What a powerful statement about the value and importance of what historians try to do, at a time when demands seem to grow ever more insistent for knowledge that can be applied instrumentally in the present. And what a powerful way of grappling with E.H. Carr’s characterisation of history as ‘an unending dialogue between the present and the past’! For Tom, history is a story of winding tracks, of obscure back lanes, of dead-ends that turn out to be nothing of the sort once inspected closely, of long forgotten streams flowing unnoticed under busy roads.

The Idea of History, What is History?, The Practice of History, The Historian’s Craft, Professing History, In Defence of History – we have many extended statements by some of our profession’s leading practitioners about what they see as distinctive and important about the study of history. A few have seen themselves as defending their integrity and purpose of their discipline from malign forces that endangered it: antiquarianism, Marxism, postmodernism. None has approached the urgency of Marc Bloch gently but firmly defending his craft as he contemplated the meaning and lived the consequences of the ‘terrible collapse’ of his beloved France in the face of German military power in 1940. The Historian’s Craft was still unfinished when he was shot by the Gestapo, but how fitting that Tom should introduce his readers to the inspiring story of Bloch in the Prologue of The Art of Time Travel. Bloch might be History’s Socrates; his career and fate inspire the thought that just as an unexamined life is not worth living, a society with an unexamined past is not worth living in.

Tom is far too intelligent a scholar to evoke a sense of history being in crisis, as if it were assailed on all sides by enemies from whom it needs to be defended. If, as Keith Windschuttle claimed in a book published in the mid-1990s, we were witnessing The Killing of History, it appears to be a very slow death and one, strangely, in which the corpse seems livelier than when it was supposedly in robust health, a variation on Weekend at Bernie’s perhaps. In any case, the evocation of an imaginary crisis is not a position from which it is really possible to celebrate the magic of history.

Tom’s starting point, it seems to me, is rather the understanding that history is a difficult art and a challenging scholarly pursuit at the same time as it is ‘an everyday search for meaning for which there is an insatiable personal and public hunger’. Greg Dening, one of the historians Tom discusses in this book, used to tell his students that history was something we do rather than something we learn. I’ve never seen this idea made more powerfully manifest than in the pages of this book. The scholars who figure here are women and men of action, even when they are sitting quietly at their desks trying to make sense of it all. They are often travellers in a literal sense – Dark in the steps of the early explorers and settlers, Keith Hancock in his stout boots in Tuscany and the Monaro, Murray-Smith voyaging to Antarctica, John Mulvaney, Grace Karskens and Mike Smith in pursuit of the buried or half-buried remains of human occupation, Karskens and Graeme Davison in pursuit of past common people, in the streets of Richmond and The Rocks, where they are eyed suspiciously by the present common people and police unfamiliar with time-travellers’ ways.

It’s characteristic of Tom’s generous embrace of the social and collegial nature of historical research that he should have chosen this original and generous way of producing a meditation on his craft and calling. There are fourteen time-travellers in these pages. Tom’s choice is personal: he is not suggesting that his selection is representative. These are historians whom he admires, time-travellers who have ‘inspired and influenced’ his own practice, scholars whose careers have intersected with his own. Nine are men and five are women. Of the fourteen, there is only one he has not met – Eleanor Dark – but he has enjoyed the hospitality of her home in the Blue Mountains, Varuna, now a writers’ house, and he has retraced many of Dark’s footsteps and met members of her family.

Some of these time-travellers have had considerable attention from others – even full-scale biographies – while others are receiving such extended attention for the first time. Either way, Tom always has something fresh to offer. We encounter Hancock in the Monaro in the 1960s and Tuscany in the 1920s rather than in the more familiar guise – at least to the world at large – of imperial historian and biographer of Jan Smuts. Stephen Murray-Smith is exploring the Antarctic, rather than the history of technical education. Judith Wright is the local and family historian acutely sensitive to the changing place of violence in the national story.

Tom does not position himself in relation to his historians in the same way in each case. Greg Dening is ‘Greg’ and Grace Karskens is ‘Grace’ but Geoffrey Blainey is ‘Blainey’. Two of the historians – Dening and Donna Merwick – figure as Tom’s undergraduate teachers at the University of Melbourne although he regards all fourteen as his teachers. Ten have spent a large part of their careers in universities but several – like Tom himself – have also worked for extended periods outside the academy, and with powerful consequences for their practice. Blainey, for instance, has worked as a freelance historian early and late in his career while Karskens built a career as a consulting historian and historical archaeologist before making a career in a university. Eric Rolls combined history with farming, and his writing extended well beyond historical works.

Most interestingly perhaps, I’d guess that possibly as few as eight and at most, perhaps ten, out of the 14, would have considered themselves historians, first and foremost. John Mulvaney and Mike Smith are archaeologists as well as historians, Eleanor Dark and Judith Wright best known, respectively, as a novelist and poet. I’m not sure about Stephen Murray-Smith, a polymath and legendary editor of the radical-nationalist cultural journal Overland, whose professional identity and rich and diverse career defy easy characterisation.

Tom does not worry over such categories. His concept of the historian as time-traveller allows him the opportunity both to grapple with what is distinctive about history at the same time as he recognises that a novelist such as Dark is indeed engaged in an endeavour ‘to understand the real past’. A scholar with a mind less subtle than Tom’s – my own springs to mind – might have tried setting Dark and Kate Grenville alongside one another as examples of the genre we call ‘historical fiction’, possibly comparing and contrasting the different kinds of truth claims they made for their writing. Tom resists this temptation. In the chapter in which Grenville figures, that on Inga Clendinnen, Tom explains that history and fiction are ‘a tag team, sometimes taking turns, sometimes working in tandem, to deepen our understanding and extend our imagination. History doesn’t own truth, and fiction doesn’t own imagination, but sometimes the differences between history and fiction are very important indeed.’ I don’t associate Tom with the use of sporting metaphors, but he moves beautifully from wrestling to tennis via dance in the next paragraph: ‘Whereas Clendinnen sees a gulf between history and fiction, I see an intriguing dance around a shifting, essential line. The good historian, like the top tennis player, plays the edges and hits down that line’. He leaves us in no doubt that while Grenville has produced something important at a time when an insistence on the violence of relations between settlers and Indigenous people was needed, it is not the same as what Dark was doing. Grenville was, as he puts it, distilling ‘a parable’ which did not allow her to participate in political debate in the way that historians were drawn into the history wars. ‘She wanted to join the game of history but to play by different rules.’ Perhaps if Tom had included in his book a chapter on Manning Clark, that comment on Grenville might also have come in handy elsewhere!

Any reader of this ‘quirky, serious and personal exploration of the art and craft of history in Australia since the Second World War’ – again, I use Tom’s own words – will come away from it with a very powerful sense that there are some very big problems facing humanity – climate change, for instance – and that historians have an essential role to play in the debates around them. This is a bold claim for a craft that Tom presents as moral, literary and imaginative, as well as rationally grounded in careful research and the evaluation of evidence. Even in this university, one is sometimes made to feel that if it can’t be counted or expressed as an equation, it’s somehow unreal.

Yet, one of the powerful themes of this book is the alliance between science and the humanities which, as Tom shows through the work of John Mulvaney and Mike Smith, has been the basis of a revolution in Australian history’s understanding of Australia’s human past. Eleanor Dark wrote A Timeless Land, and she and her family took over a cave in the Blue Mountains to which they gave a name that sounded Aboriginal to them but was actually a combination of family names. Yet as Tom points out, The Art of Time Travel also ends with a cave, this one in the central Australian desert, which is the basis for Smith’s important work demonstrating a 30,000-year Aboriginal occupation of the continent’s heart.

This radical extension of our appreciation of the length of Australia’s history –of ‘deep time’ – has occurred within the lifetimes of even middle-aged people in this room, including within Tom’s own. There is a remarkable paradox here, of the vast expanse of time – one extending over millions of years to the history of Gondwana and beyond – as well as of the most rapid changes in our historical consciousness as we seek to get our heads around the mind-bending numbers involved. And one of the big ideas in this book is that scholars in Australia have been great contributors to global conversations about these matters of geological, environmental and human history. The message is surely that by pursuing the stories of our own past with skill and passion, we have something valuable to contribute to humanity. That’s a powerful defence of Australian history as well as a timely one.

Tom’s book will be read with pleasure by people who read but do not write history. He probably won’t get a letter quite like the one received by Eric Rolls which, I think, most of us would recall as the highlight of one’s career, greater than any mere literary prize: ‘This is the first book I have ever read. Thank you for writing it. I enjoyed it so much I am now going to try reading other books’. Nonetheless, The Art of Time Travel will explain to such readers better than any other book I know what it is that historians do, and why what they do should matter to everyone.

It will also be read for its wisdom and inspiration by Tom’s fellow-historians. As one of this breed, I should add that it also alerted me to some large gaps in my own reading of Australian history, gaps that I’ll now do my best to fill on Tom’s powerful recommendation. I suspect it will also become Tom’s fate – not an entirely unpleasant one – to have his book chopped into chapters for student reading, in history extension courses in high schools, as well as historiography courses in universities. The marvellous Prologue, in particular, may well take over a great deal of heavy-lifting work from the opening chapter of Carr’s What is History? It’s surely earned a rest after more than half a century of faithful service.

A very large number of us who are Tom’s colleagues in the historical profession, if we were asked to come up with the 14 who had taught and inspired us most, would include someone who does not appear in his list: and that, of course, is Tom himself. Right from that first book on Beechworth – I’ve been borrowing it from colleagues and libraries for years but now have my own thanks to a second-hand bookshop in Ballarat – Tom has been a historian of striking originality. We can feel privileged to have this reflection on his many years of research, thinking, writing and teaching. But I have the additional privilege, as well as the pleasure, of launching The Art of Time Travel: Historians and Their Craft here in Canberra, among Tom’s family, friends, colleagues, students and many admirers. My warm congratulations to the publisher, Black Inc. and Chris Feik, and to the author, Tom Griffiths, for a great achievement. I’m confident that its voyage into the future will do much to enrich our history.

Share this post

About the authors

Tom Griffiths is the W K Hancock Professor of History at the Australian National University and the author of Slicing the Silence: Voyaging to Antarctica (2007), Forests of Ash: An Environmental History (2001) and Hunters and Collectors: The Antiquarian Imagination in Australia (1996). His books and essays have won prizes in literature, history, science, politics and journalism, including the Prime Minister’s Prize for Australian History, the Alfred Deakin Prize for …

More about Tom Griffiths

Frank Bongiorno is the author of three acclaimed histories: Dreamers and Schemers, The Eighties and The Sex Lives of Australians. He is professor of history at the Australian National University and president of the Australian Historical Association.

More about Frank Bongiorno