News

News > Speech

U.N. International Holocaust Remembrance Day Commemoration

A Testimony by Baba Schwartz, presented at the U.N. International Holocaust Remembrance Day Commemoration at the Jewish Holocaust Centre in Melbourne on January 30th 2017.

Let me tell you about a Holocaust survivor who lives in Vienna.

She is 89.

Her name is Gertrude.

We don’t know her surname.

She lost all her family in Auschwitz

Last November she made a video.

She warned Austrians not to vote for the far-right party.

Her video was seen by almost 3 million people. She made news worldwide.

She said that this party: “aimed to bring out the worst in people”, like the anti-semitism of the Nazis in the 1930’s.

She said:

“This is probably my last election… But young people have all their lives ahead of them and they need to make sure that they are doing the correct thing”.

“The thing that bothers me most (she said) is the denigration of others.

She went on:

“I have seen this once before… and it hurts and scares me”

When you see the video, you’ll understand its power. Her statement is so direct, so matter of fact. She doesn’t call up the big issues of the Holocaust. She goes to the seeds of it. The seeds of evil. She can see how it can start with just words.

We are having that debate here, in Australia today.

Is it ok to be a bigot in the interest of free speech?

Gertrude says it certainly is not.

Google her! Simply type in: Gertrude Austria.

I am also 89.

I too was in Auschwitz.

Listen carefully to us, for we are the last of the survivors. The last of the witnesses.

I was born in Nyirbator; a rural town of 12,000 people in Eastern Hungary.

3000 were Jewish.

My childhood years were happy. I loved my little family, my gentle father, my lively mother, and my two sisters.

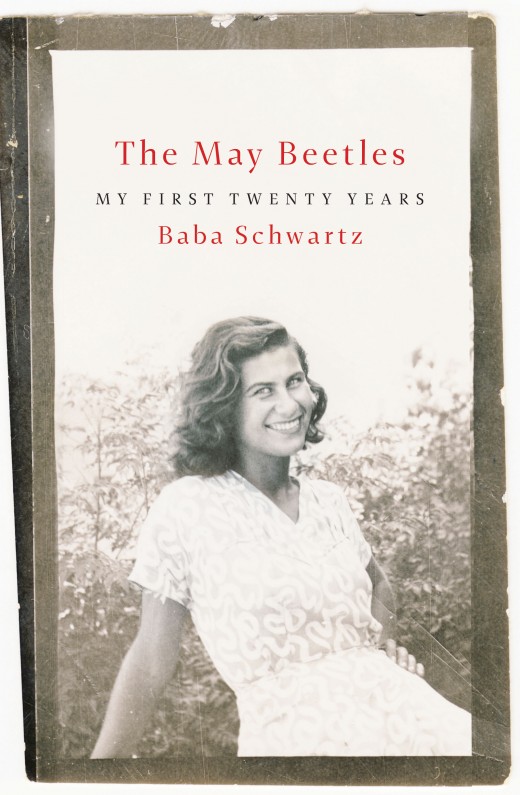

Let me quote a passage from my memoir: The May Beetles:

“This life I am revealing – this father, this mother, this family – is the life I would wish for everyone. No harm in any of us, but instead a sense of the inexhaustible delight in the world. Yes, if I could bestow a gift on others, it would be to live as my family had before the great darkness. Let everyone know what it was like to bask in the love and care of such a mother and such a father. Let everyone know what it was like to have Erna and Marta as sisters”.

Whilst we were observant Jews, we lived in peace and harmony with our non-Jewish neighbours.

By late 1930’s the anti-Jewish laws were introduced in Hungary. Emboldened, Hungarian soldiers would march through our town, singing loudly:

“Hey, Jew, hey, Jew, hey, you stinking Jew

What are you doing here amongst us Hungarians?

Under your side-locks lice are crawling

Your mother Zaly was smuggled into our land

In a sack on your father’s back.

And as time passed, the words became more dangerous:

They sang:

Because the Jew is of a kosher kind

It feels so good to hit him hard.

Amongst our many close non-Jewish friends were the Szucs family. The parents with the parents. We three children with their three. We almost lived in each other’s homes. This warm friendship between our families remained un-spoilt until one day, in 1938, we saw the Szucs boy in the street. As we past him, he looked at us and shouted: ‘Stinking Jews!”

He was influenced by the hateful sentiments that had become commonplace.

It started with words.

And then, the actions.

The German army marched into Hungary on the 19th of March1944.

The Hungarians, well primed in the hatred of Jews, became their willing helpers.

The Germans left the prosecution of the Jewish population to the Hungarians.

They were obsessed with their ‘Jewish Question’, and worked on nothing but their ‘Jewish Laws’.

It all unfolded fast, with new shocks every day.

All Jews had to surrender their jewelry and radios to the authorities. All Jews had to wear the yellow star.

My grandfather, Yitzchak Kellner, was a community leader, a man of great dignity. He was beaten almost to death for defying the orders of the Hungarians.

Then the entre Jewish population: 3000 souls, was ordered to pack for a short trip.

They were all taken to holding camps for about a month.

And then, three days of unspeakable horror, in cattle wagons, to Auschwitz. Crammed in, 70 to a carriage.

We were all exhausted by the ordeal, driven almost mad by the continual dread, and the endless clatter of the metal wheels.

When the train finally came to a halt:

We did not know, we could not have known - that we had arrived at the gates of hell.

My beloved, gentle father, Julius Keimovits, was gassed in that accursed place.

My late husband Andor, Zichrono L’vraha, lost his entire family.

Gertrude of Vienna lost her entire family.

So many lives were taken for no reason. Murdered by the Nazis and their enthusiastic collaborators: Yimach Shemam.

My mother Boske, my sisters Erna and Marta, and I, we survived.

We survived by good fortune, and we survived by the iron will and courage of my mother.

We survived hell.

From Auschwitz we were taken to a number of other camps; slave labor for the German army.

The fear, hunger, freezing cold, and exhaustion were unrelenting.

Then the death march.

The Russian Army was approaching.

The Nazis retreating.

The SS were marching their bedraggled slaves Westward.

As I describe in my book:

“It was winter in Poland, the wind cut us to the bone as we marched. We wore wooden clogs, without socks. The snow hardened on the wood, creating a wedge, and often we slipped and fell onto the frozen ground. We helped each other up. ‘Girls try to keep your feet’, our mother said. Keep walking. We all knew that the SS would drag us aside and shoot us if they saw us fall.

I looked back once and saw an SS guard holding a woman down while another soldier shot her in the head. Then the body was thrown to the side of the road. I felt sick. We passed many bodies lying on the roadside – executed women from groups ahead of us.”

My brave mother and sister Erna hatched a plan. We had to escape. And we did. We made a run for it.

Before long, we were liberated by the Russian army – and that’s another story.

We eventually made it back to our town in Hungary. Of the 3,000 Jews, only about 130 returned.

I married Andor; we had a son.

We made aliya; we had another son.

10 years later we migrated to Australia; we had our third son.

This country has been good and generous to us. It has been a free and just country. Let’s keep it that way.

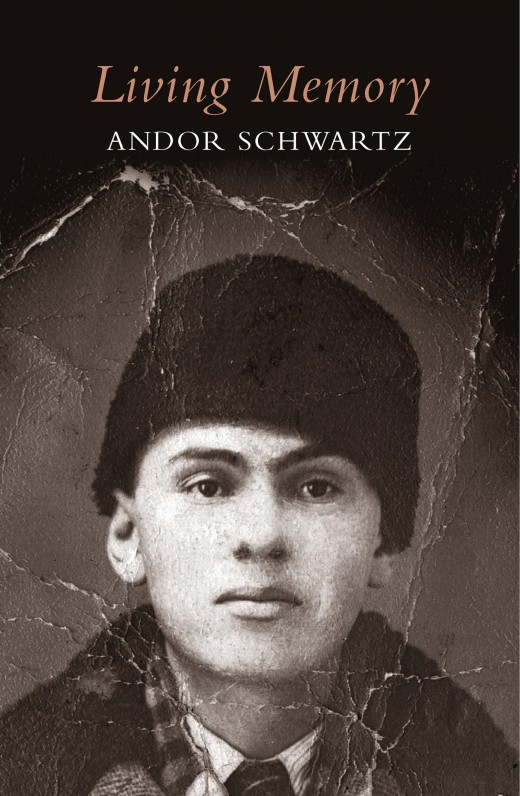

When he was 79, Andor, my husband, wrote his memoir. He called it Living Memory.

He was driven to record the lives of his family and friends who perished.

Let me quote him:

“Writing it was a miracle. My pen was pushing ahead with full speed. I didn’t have to think, names and dates were coming back with the speed of fire. Sentence after sentence, all making sense, all of them correct. It was written with my tears. I broke down many times… All my dear family, one after the other, all came back to me.”

Can it all happen again?

You bet it can!

We might not be the next, but some group will be.

So let’s keep telling our stories.

Let’s continue to caution against discrimination and hate.

Let us all watch our words, before they turn into actions.

As our sages said in Pirke Avot:

‘Chaim vamavet beyad halashon’

‘Life and death in the hands of the tongue’

In 2004 my husband and I funded a new path at Yad Vashem.

The path is known as the Path of Remembrance and Reflection. We constructed three headstones along the path – to our loved ones who have no graves, no markers of ever having existed.

When you next visit Yad Vashem, walk along this path and you’ll first see a headstone, in memory of all the murdered Jews of Hungary.

Then one in memory of my husband’s family – his father Moritz; his mother Kato; his brother Imre; and his dear little sister Erszike.

And across the path, stands the third headstone, in memory of my dear father: Julius Keimovits, who perished in Auschwitz.

At the consecration of this path, and the three headstones, now twelve years ago, both Andor and I talked.

This is what I said:

Survivors of the Shoah carry

An extra burden of pain, sorrow and anger.

The weight of the load does not diminish

With the passing of the years.

To Yad Vashem: we come to remember.

I then continued to speak directly to my late father, Zichrono Le’vracha, and this is what I said:

Father, Apukam, I need to speak to you.

Now that your name is engraved on that stone

I feel your immediate presence.

I feel it as strong as then, when

Our eyes met for the last time

At that accursed place at Auschwitz.

Do you remember?

Three hellish days and nights on the train of the damned,

Not enough place to sit for all of us,

You stood throughout that grim, fearful journey,

So that we could sit, your beloved ones,

Your adored wife and treasured three daughters.

You lived only for us, we were all your life.

I do remember.

We were brought to Auschwitz,

Sheep ready for slaughter.

Everything happened with lightning speed,

Men and women were separated,

Then a selection, this to right that to left.

Mother and we girls with the living were sent.

But no way for us to know to which side you went.

In a huge hall brisk orders barked:

All strip naked,

Drop your clothes where you stand.

Then inmates sheared our heads

And gave us rags to wear,

And from that shower on a warm day of May

We came out altered, humiliated, shamed.

To C Lager they took us, empty, yet to be filled,

Stood there for hours in front of our barrack.

The air was thick with smoke, the smell of burning flesh,

And old inmates told us unspeakable truth.

Then

A company of men passed, unforeseen, surprising.

I ran to see: were you amongst the men?

You wore prisoner’s stripes and a prisoner cap,

Easy to recognise, you looked like your old self.

I, with boundless joy,

Arms raised called out to you:

Father, Apukam, look at me, here I am.

You looked at me, puzzled,

Questions rose in your eyes.

I did not know why, I did not see myself.

A crazy woman waving,

Hairless and in rags.

Do you remember?

And I kept on screaming,

Here I am look at me!

My voice did it? Perhaps,

But recognition came.

Your eyes darkened with endless sorrow,

You could not bear the sight,

Buried your face into your hands

And shuffled away, sobbing.

The last time I saw you.

I was sixteen then and you were forty-eight,

In the prime of your life, clever, capable, smart,

Lipe was with you, your wife’s younger brother.

How you looked after him,

Fed him, protected him, even in Buchenwald.

Duty bound you took him, for false promises came

From the murderers’ mouth, Y’mach Sh’mam,

Promises of more food at a better new place.

And on the second day of Sukkot, in 1944,

They took you back to Auschwitz to be sent up in smoke,

You, and your charge, Lipe, your adored wife’s brother,

With all the others.

Father, do you hear me?

Good tidings I bring you now,

From Eretz Yisrael, from Yerushalayim,

I am here to greet you, a content old woman,

By my side my husband of fifty-seven years.

He is good and clever, dutiful and caring,

With a warm heart and an open hand,

And we all love him.

Look at our three sons now, Moshe, Alan, Danny,

Denied the joy of having grandfathers.

They would make you so proud,

As they make us parents.

Their wives and their children

Stand beside them also.

All are strong, all are bright,

Yet loving and tender.

You would love them, I know.

I hope that you hear me,

Apukam, dear Father

Yechiel Ben Rafael Menashe

Zichroncha Livracha, Alecha Shalom

Share this post

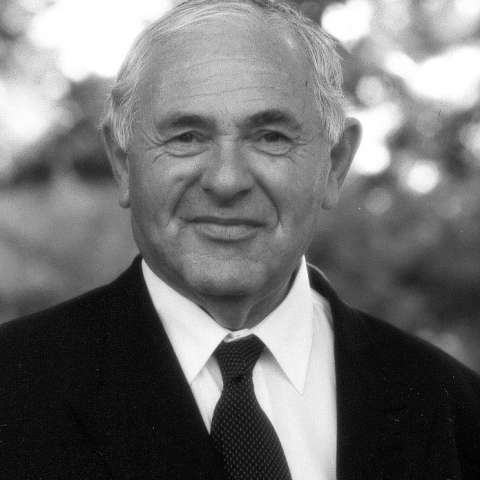

About the authors

Baba Schwartz was born in Hungary in December 1927. A survivor of the Holocaust, she migrated to Australia in the 1950s with her family, settling in Melbourne. The author of the memoir The May Beetles, she was also a born baker, renowned for her superb cakes and pastries.

Author photo by Caitlin Muscat

More about Baba Schwartz

Andor Schwartz was born in Hungary in 1924. He survived World War II in Budapest – although his whole family was killed – before marrying Margaret (Baba) Keimovits, one of the few survivors from their area. They fled to Israel when the communists came to power in 1949. After ten years of working the land, they migrated to Melbourne, where he became a dairy farmer and a successful property developer.

More about Andor Schwartz