News

News >

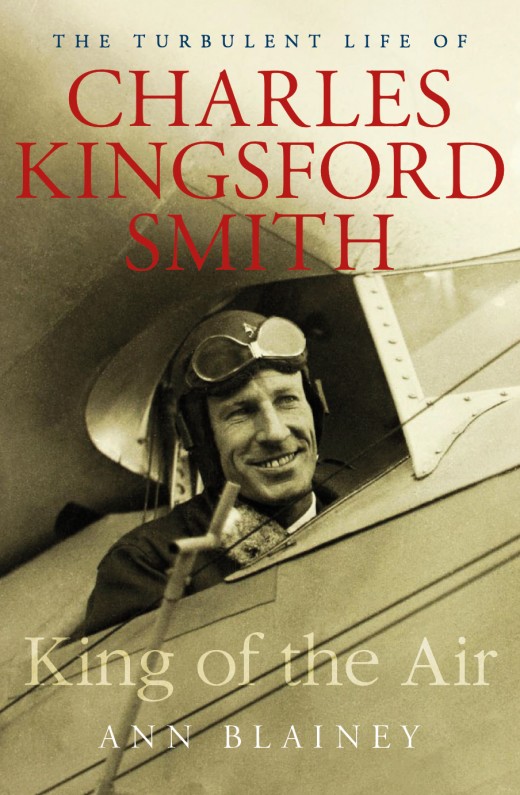

Extract: King of the Air

‘We absolutely won’t fail.’ Read on for an extract from Ann Blainey's King of the Air.

Grey curtains of mist competed with sunshine on the morning of 31 May 1928, as a throng of several hundred supporters and reporters gathered at the Oakland airfield to wish the Southern Cross and its crew godspeed. Captain Hancock, so unassertive as to be almost anonymous, stood among them, as did Harold Kingsford Smith. Also present were two couples who had befriended the young Australians when their fortunes were at their lowest: a Glendale surgeon, Dr F.T. Read, and his wife, Ann, and a furniture retailer named Robert Wian and his wife, Cora. Ann Read presented Smithy with a bunch of Californian poppies and a good-luck horseshoe, which he added to his lucky photograph of Nellie Stewart and a Felix the Cat brooch that he wore on the front of his cap. The brooch had been given to him by a ‘romantic’ young lady, he blushingly told a reporter.

As might have been expected, romantic young ladies were in the crowd; one reporter noticed three of them pressing kisses on Smithy as he prepared to enter the cockpit. Almost at that same minute, the mother of Alvin Eichwaldt, a flyer killed while searching for the missing Dole Air Race pilots, tearfully presented her son’s silver ring to Smithy to wear. ‘The incident touched me deeply,’ he wrote later, ‘and I gladly assented to her wish.’ Turning to the eager reporters, he confidently made a final statement: ‘I’ve waited many weary months for this day. We are fully prepared and if we fail, I haven’t a single regret. We absolutely won’t fail.’

At about eight forty-five, Smithy and Ulm climbed the steep ladder and clambered into the cockpit, while Warner and Lyon entered the rear cabin through the door in the fuselage. Cecil Maidment cranked up the engines and the Fokker began to move. A minute or so later, one of the engines faltered. Smithy halted the plane briefly, then started it up again, and this time all three engines ‘roared in harmony’: ‘no Wagnerian chorus,’ wrote Smithy, ‘could have given us greater pleasure.’ The overladen Southern Cross rose ponderously into the air, pursued by a fleet of small planes carrying movie cameramen. ‘I experienced a sensation of relaxation and relief,’ Smithy remembered, ‘and at the same time a tremendous elation at the prospect before me.’

The sun now broke through a height of mist, giving ‘rosy promise’ of fair weather. As they flew at 1100 feet past the city skyscrapers and on towards the Golden Gate Bridge, they observed twirls of mist drifting seawards, looking like ‘light smoke’. During take-offs on the endurance flights, Pond and Smithy had joked that angels sat atop the bridge, ready to scoop up their souls if the Southern Cross crashed. Today, Smithy saw no angels but ‘felt that the gods had smiled on us’. He turned to Ulm seated beside him, and they shook hands ‘in mutual congratulations’.

Despite the euphoria, both were aware that twenty-seven hours of flying lay ahead of them, during which neither could expect much in the way of comfort. To lessen the weight, they sat on wicker chairs, bought from Wian’s furniture store in Glendale. In the custom of the time, the chairs were not bolted to the floor, and the occupants did not wear seatbelts. In turbulent air, men and chairs bounced around the cockpit and the cabin.

Up in the cockpit, Smithy and Ulm sat side by side, with the dual controls in front of them. Theoretically, Ulm was the relief pilot, and he had actually given himself the title of co-commander, but with only basic training and no pilot’s licence he was not allowed to take off or to land the plane. He had sufficient skill, however, to maintain its course while Smithy slept – which was fortunate, since Smithy, as the true commander, needed regular rest to stay alert. Far shorter than Ulm, he did better than his co-commander at sleeping in his wicker chair, although he later admitted that his sleep was fitful.

Often it was too windy to sleep. The small, silken Australian flag, which hung between the petrol gauges as a good-luck charm, was ripped to tatters by the air that rushed through the cockpit. The cold could also bite deep. Although he and Ulm were dressed semi-formally for take-off, wearing leather jackets, ties, riding breeches and boots, they gratefully pulled on fur-lined flying suits and caps and goggles once the sun went down. The rear cabin was more spacious than the cockpit, being eight and a quarter feet long and six feet high. Its occupants could huddle on the floor and sleep, or stand upright and walk, and both actions were accounted great blessings. The air, however, was as cold as in the cockpit, for the cabin was no more than a tubular steel frame covered by thin fabric held in place by criss-crossing bracing wires. How bitterly Lyon and Warner regretted their naive assumption that they should dress for the tropics. The blue serge suits and smart straw hats they had chosen to wear were no match for the freezing winds. Nor was cold their only enemy. In cockpit and cabin alike, ‘the roar of the motors assailed their ears with the pound, it seemed, of sledgehammers’. Not even plasticine earplugs could make the din tolerable. On the other hand, those thundering engines were keeping them aloft, so it was also a comforting sound.

The absence of a toilet created a problem. The aviators made do with bottles, the contents of which they tipped out the window. Possibly on this long trip, and certainly on later ones, Smithy took binding medicine as a preliminary to the flight. But perhaps their keenest privation was being forbidden to smoke. Deprived of cigarettes for fear of fire, they suffered the gnawing pangs of nicotine withdrawal. In a joking Morse code message sent to the editor of the Los Angeles Examiner, Ulm wrote: ‘Smoke two cigarettes at once for me – Smithy and I both crave the odd smoke.’

Through that first morning, calm weather and the excitement of being airborne kept their discomfort at bay. However, with each pass- ing hour flying became more ‘monotonous’, which did not suit Smithy. The ‘blue sea below us’, he wrote, and ‘the blue vault above us, and the overpowering roar of the engines oppressed one’s spirit’. Fortunately, he and Ulm were enlivened by ‘cheery little messages’ sent by Lyon, ‘who maintained a regular delivery of notes which told us where we were, and at other times asked us most unexpected question’. These notes, mainly ‘personal chaff of a forcible kind’, came pinned to the message stick. Ulm found it ‘a strange experience for four men to sit in such a confined space and so near to one another, and yet be unable to exchange a spoken word’. Even so, many written words were exchanged inside the cabin, and many more were sent in Morse code, the era of radio voice-messages lying in the future. Every hour, Lyon calculated their navigational position and sent it by message stick to the cockpit, and at the same time Warner broadcast it to the world in Morse code, on the Southern Cross’s special radio call sign of KHAB.

Now that they were familiar with their exciting new transmitter and receiver, Warner and Lyon became radio addicts. Between them, they knew naval radio operators across America and right around the Pacific, and scores of friends were called up, even though Ulm had expressly forbidden private transmissions. Pressing away at the transmitter keys, they cracked jokes, exchanged gossip, flirted with former girlfriends and described scenes aboard the Southern Cross in thrilling detail. Smithy and Ulm also sent messages to their families; Smithy also sent a special message to an Emma Myers of San Francisco, who may have been the romantic donor of the Felix the Cat badge. Charmed by the radio chatter and the banter that Lyon kept sending on the message stick, Ulm wrote in the plane’s log: ‘We’re as happy as hell cracking “wise cracks” ad lib.’

News in Morse code went regularly to the Los Angeles Examiner and, of course, to the Sun newspapers, which received it by way of the Amalgamated Wireless Association’s receiving station at La Perouse, in Sydney’s south. There, operators relayed messages to the Sydney Sun, and to radio station 2BL, which, as the flight progressed, began to share its news with the Melbourne station 3LO and the Queensland station 4QG. The notion of exclusive newspaper rights was nonsense, for anyone with a sufficiently powerful receiving set could listen in. Associated Press – among others – was poaching and spreading the news freely. Ulm found himself apologising to the Sun and the Examiner for cir- cumstances beyond his control.

At the radio stations, the Morse dots and dashes were not only passed on to the listeners as they came across the airwaves, but were also translated into words so that the station announcer could read them aloud. As one reporter put it: ‘Thousands of persons, comfortable before their own firesides, were thus brought into direct touch with the four gallant airmen who were battling their way across the uncharted air.’ Listeners stayed glued to their receiving sets for hours, and as the flight progressed it was not uncommon for groups of friends to spend the night together ‘listening in’. One woman claimed to have taken her headphones to bed with her, only to be awakened, a few hours later, when ‘cheers given at the broadcasting station came through the pillows’. In America, Australasia, the South Pacific and even South Africa, dots and dashes from the Southern Cross became a gripping focus of attention. Smithy and his crew were making social history as well as aeronautical history.

Since Smithy’s parents could not afford a radio, William spent his nights listening to his neighbour’s receiving set. At important moments, he would run next door to fetch Catherine, who – though equally anxious – preferred the quiet of her room to the tension of a public vigil. She was a woman of strong religious faith, and she put her trust in God. Ever since Smithy’s near-drowning at Bondi, she had wondered if the Almighty had saved her boy’s life for a purpose. Was it his destiny to cross the Pacific? She spent much of the night praying for his safety and success.

As the hours passed, the aviators’ early confidence gave way to unease. Smithy had hoped to maintain an even height of about 600 feet for most of the crossing, which would help him conserve fuel, but it was proving harder than he had foreseen. Great buttes of cloud lay in their path, and rather than fly blindly through them, he chose to climb above them, even though this meant that ‘the thirst of the three engines became as keen – as insatiable – as that of a man lost in the desert’. He began to fear that those thirsty engines would exhaust their fuel before they reached Hawaii, and terminate their adventure fatally.

Smithy and Ulm made hasty calculations about their fuel reserves, but these proved too inconclusive to calm their nerves. Fear began to unsettle their emotions. ‘We ran a gamut,’ Ulm remembered, ‘between black pessimism and wild exhilaration.’ Meanwhile, the light was fad- ing and it was time to climb again, for, in that era, low night-flying was deemed dangerous, especially above an ocean. ‘It was safer up there in the darkness,’ Ulm remembered, ‘particularly if we swept into a patch where blind flying was necessary.’

At the height of 4000 feet, they saw scenes of rare beauty. An excited Warner described some of them to his radio listeners. ‘The moon shining down is casting our shadow into the clouds,’ he reported in Morse code: ‘I’m sending this as I see it.’ The burning contents of the Fokker’s exhaust pipe inspired another of his Morse descriptions. It resembled ‘a livid trail of flame’, spitting from the big blue monoplane as it tore its way over thousands of miles of ocean.

Just before midnight, they flew into a squall. For a quarter of an hour the plane bumped and jolted, scaring the wits out of Lyon and Warner, who, though they were used to rough seas, were not used to rough air. Lyon was playing cards when the squall struck and he was hurled across the cabin. Hurled also was the bubble sextant, which broke its bubble in one fierce jolt. To escape the storm, Smithy climbed to 5000 feet – into a moonlit realm where the eerie shadow of the Southern Cross moved like a ghost plane at their side. Lulled by the unearthly beauty of the scene, they fell into a kind of reverie. ‘There was no world,’ Ulm remembered: ‘We were sailing lazily on the Milky Way.’

Further worries led them back to reality. Hours previously, they had lost contact with the US Army radio beacons, in California and in Hawaii, which projected beams towards each other, thus assisting ships and planes to remain on course. Since the sextant was broken and the beams were lost, it was crucial to check their position by contacting the ships at sea beneath them. Although the shipping lanes were said to be busy, it was well past midnight before they sighted a vessel. Fortunately it was the Maliko, whose captain knew Lyon. Through their Morse banter, the two old shipmates calculated that the Southern Cross was on course. A little later Warner contacted the steamship Manoa, which also happily confirmed their position. From the same ship Lyon also learned the latest American baseball scores.

In this fashion the night passed, and by six am they were exhausted, deaf and chilled. They would have given almost anything for a smoke – and more than anything for a sight of the Hawaiian islands. Their fear of running out of fuel returned. As the sun came up, Smithy descended to 2000 feet to look for land, and seeing none, became increasingly anxious. One of the wind generators had failed, and the radio batteries were fading.

By nine o’clock everybody was on edge. Smithy saw what he hoped was an island, only to receive Lyon’s emphatic rebuke that he knew the Hawaiian islands ‘like the back of his hand’. As it certainly was not an island, an argument ensued. In the close confines of the cabin, a nervous Warner, seeing Lyon’s angry face, snatched a piece of paper and wrote on it: ‘Are we lost?’ Grabbing the pencil Lyon scrawled in reply: ‘YES.’ Ignoring the low batteries, Warner began to transmit radio messages to the world, announcing that they were lost and almost out of gas.

The island proved to be a cloud. Confusion reigned until Lyon made an excellent sun shot with his damaged sextant, and Warner managed to receive a faint but reassuring radio bearing from Hilo, on the island of Hawaii. They were on course and almost there. Just before eleven am, on Warner’s insistence, Smithy climbed to 4500 feet to extend their observation, and Lyon saw a brown and white bulge in the distance. Taking a quick bearing, he realised it was the snow-capped volcano Mauna Kea, on the island of Hawaii. Overjoyed, he sent word to Smithy, who quickly replied: ‘Damned good work Harry, old Lion. Keep on doing your stuff – Smithy and Chas.’ Lyon replied with a joking version of Smithy’s RAF slang: ‘If we get a cigarette and a cup of coffee we’ll feel like flying back – ha, what, Old Top.’

Soon after, they sighted the island of Oahu, green and fresh in the morning sun, and high above Diamond Head they spied army planes waiting to escort them in. A loudspeaker at the aerodrome, Wheeler Field, which an hour or so before had kept the 15,000 welcomers on tenterhooks by broadcasting Warner’s anguished messages, was now hailing their imminent arrival.

Just after midday – ten am, Hawaiian time – the Southern Cross swooped low over Honolulu. Twelve minutes later it touched down. The crossing had taken twenty-seven hours and twenty-five minutes, leaving them – although they did not then know it – sufficient fuel for another three hours of flying.

As Smithy and Ulm climbed down from the cockpit, they were deluged by reporters. Amid the crush, an attractive young woman attached herself to Smithy. Had he been frightened that they might go down in the sea, she asked him sweetly. He was exhausted, dazed and so deaf from the engines he could scarcely hear her, but he could not resist her innocent charm. Perhaps remembering his near-drowning in childhood, he gave a brilliant answer. ‘Hell no, madam,’ he retorted. ‘I was born to be hanged, not drowned.’

King of the Air is available now. Click here for more details.

Share this post

About the author

Ann Blainey is the author of King of the Air and the acclaimed I Am Melba, which won the 2009 National Biography Award and was the most popular book in the 2009 State Library of Victoria Summer Reads program. Her other books include biographies of Leigh Hunt and the Kemble sisters.

More about Ann Blainey