News

News >

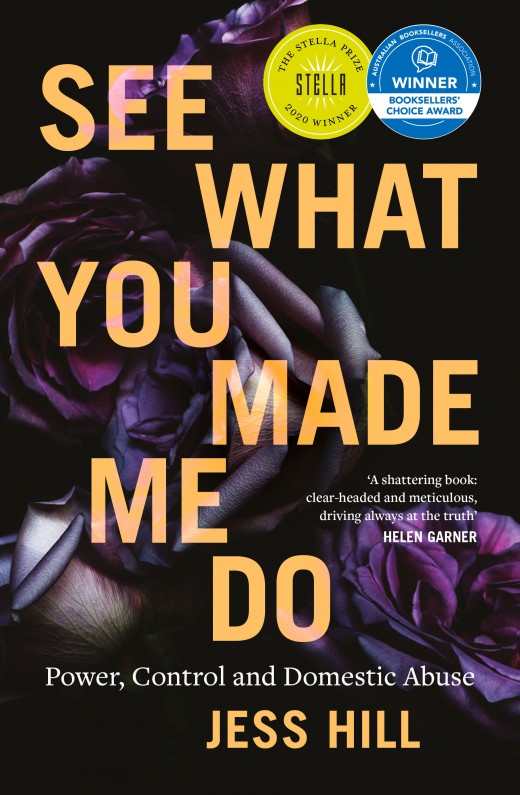

Read an extract: See What You Made Me Do

In the thirty-nine days before she was murdered, Kelly Thompson called the police thirty-eight times. Read on below for an extract from the chapter 'State of Emergency.' CW: distressing content and violence.

Often, the stories with the worst endings are not blockbuster horror stories, but catalogues of negligence, laziness and procedural error. These are perhaps the most important cases for us to grapple with.

Just after midnight on 8 February 2014, Norman Paskin called police to report that there was a man inside the house of his neighbour, Kelly Thompson, who shouldn’t be there. For over two hours, Norman had seen his former neighbour, Wayne Wood, drive past Kelly’s house repeatedly in his white van. He knew something was up – in the past month he’d seen Wayne at the house several times with a police escort, removing items from the garage. That night, when Norman saw Wayne park his van some distance away and approach Kelly’s house on foot, he called police and told the junior constable on duty that he suspected there might be an intervention order against the man now inside Kelly’s house.

A call about Kelly Thompson’s address should have raised immediate red flags at Melbourne’s Werribee Police Station. Over the last thirty-nine days, Kelly had called the station thirty-eight times. She had first come to police attention just a few weeks earlier: Wayne had attempted to choke her, and when she managed to escape he had chased her down the street in his car. A passing driver, Steven Hall, saw a distressed woman walking quickly down the street and had the presence of mind to stop and ask if she was okay. ‘Not really,’ Kelly replied. ‘My partner tried to strangle me.’ As Kelly was talking to Steven, Wayne swerved his car around and trapped her between Steven’s car and his own, then started shouting at Steven to ‘get the fuck out of here’.* As Wayne raved and yelled, Kelly leaned into the passenger window and whispered her address to Steven’s girlfriend, and asked her to call the police.

At around 8.50 pm, emergency services relayed these details to Werribee Police Station:

Female versus male in a vehicle. The female asked the complainant to call the police for her. The complainant’s not involved. She’s stated her partner’s tried to strangle her. The male came around in a vehicle. He told the complainant to leave.

Dispatching a car, the police radio operator said it was ‘just a domestic’.

When the two constables arrived at the house, Kelly looked ‘a bit dishevelled, like she had been crying or very upset’. Police separated the couple to question them. Wayne, ‘upset’ but ‘calm’, told his story: they’d had an argument over business, and he had just been trying to get Kelly to come back to the house after she walked off saying the relationship was over. The police appeared to accept that this was just a lover’s tiff: as one of the attending constables later testified, ‘he wasn’t violent towards us at all and he didn’t seem violent towards her’ and ‘none of them had any injuries on them’. Kelly refused to explain what had happened, insisting she wouldn’t say anything until their business partner arrived. But instead of waiting, the two constables simply advised Wayne to stay somewhere else for the night ‘to allow both parties to calm down’ and told Kelly that if she wanted to take out an intervention order, she could apply for one at the Magistrate’s Court.

It’s police policy to gather statements from all available witnesses, but the constables did not interview Steven Hall or his partner, who had called Triple Zero. If they had, they would have heard how Kelly looked and sounded when she disclosed being choked, and learned of her whispered request to call police – a clear indication that she was frightened of Wayne. They would have also had witness testimony of Wayne’s erratic driving, and his attempt to pin Kelly between two cars – something that would likely have warranted an investigation into separate charges and cast a very different light on Wayne’s story. All of these missed opportunities – and the laziness of the constables’ response – set off a chain reaction that would tragically compromise the police response over the coming weeks, until the night Norman Paskin called to report that Wayne was inside Kelly’s house.

When the constables returned to the station, they did what all police do after a family violence incident: they filled out a form. The L17 form, as it’s known in Victoria, is the ‘cornerstone’ of the police response: subsequent police rely on it to tell them the victim’s level of risk, the kind of support they may need and whether the perpetrator is likely to reoffend. The constables wrote up the incident exactly as Wayne described it: as an issue regarding ‘relationship breakdown and business problems’. Kelly was described as ‘not fearful’, despite her clear refusal to speak about the incident in Wayne’s presence. With no mention of the choking – a known red flag for future homicide – the matter was set as a low-risk case. As is policy, the L17 form was then sent on to the Wyndham Family Violence unit for review and follow-up. There, another constable reviewed the information, which the two attending members had assessed as ‘minor in nature’ and ‘unlikely’ to present any future risk. That constable followed every protocol to the letter: Kelly was referred to a family violence service and, after he called and left a message on her phone, the incident was marked as complete. Kelly didn’t return the call.

Meanwhile, although Kelly had made it clear the relationship was over, Wayne became more controlling. At a local pool competition a week later, Kelly complained to a friend that Wayne wouldn’t even let her go to the toilet without him. Afraid that Wayne’s behaviour was escalating, Kelly asked her brother Patrick to come and get her. When Patrick arrived, Wayne confronted him: ‘What, are you here to belt me?’ ‘No,’ said Patrick, ‘I am here to take my sister – she doesn’t want to be with you.’

Two days later, Kelly applied for an intervention order. ‘He tried to strangle me 1/1/2014,’ she wrote on her application. In notes taken by the intervention order registrar, Kelly says, ‘he is jealous and possessive and I don’t believe he will leave me alone and I fear he may kill me’. Given how serious the threat was, the magistrate granted her an interim order straightaway, and the order was faxed to Werribee Police Station. Over the next five days, Kelly – too afraid to return home until the order was served – called the station ten times to ask when it would be served. It took five days – a delay that almost certainly wouldn’t have occurred had police applied for the order on Kelly’s behalf.

Within a week, Wayne had breached the order, approaching Kelly when she was out to dinner with friends. Kelly reported the incident, and police called Wayne into the station for questioning. But despite Wayne admitting he had breached the order, police did not charge him, telling him only that he may be summoned to court later. There is no ambiguity in police protocols: breaching an intervention order is a criminal offence, and breaches – no matter how small – are to be strictly enforced. Yet even when Wayne breached for a second time, he was not arrested. Kelly confided in a friend that police told her it took ‘ten breaches’ before they could arrest someone for breaching an intervention order. While Kelly’s status in the police files remained as low-risk, Wayne was calling police repeatedly to accompany him to collect property from the house. This kind of controlling behaviour should have rung alarm bells, as Victoria’s assistant police commissioner, Luke Cornelius, would later testify: ‘I would’ve expected this issue to be the subject of some discussion back at the station.’ Meanwhile, Wayne was stalking Kelly’s friends and hiding in her backyard. According to one friend, Kelly had called police to report that he was lurking outside the house and appeared to show up everywhere she went. ‘She told the police that on numerous occasions,’ they said. There is no police record of Kelly reporting any of these breaches.

On 8 February – the day neighbour Norman Paskin called police – Wayne attended a reunion of friends. He was not drinking but was sweating profusely and looked ‘devastated’. To one friend, he said he was going to ‘do the business partners [who had ripped him off ], Kelly and then himself’. To another, he said, ‘I will get her, you know.’ Wayne couldn’t read or write, and since the business had failed, he had no choice but to go on welfare. ‘I’ve lost everything,’ he said.

While Wayne was at the reunion, Kelly was at lunch with her friend and his wife. They urged her to stay with them – they could help her move so that Wayne would not find her. Kelly agreed, but said she needed to go home and do a couple of things first. She was also worried about her beloved dog, Roxie.

That night, Norman was out late, tending his garden, when Wayne walked straight past him ‘without any kind of acknowledgement’. Norman thought he must be drunk: Wayne was staggering, ‘seemed unaware of the things around him’ and was staring intently at Kelly’s house. After he drove around the area a few more times, Wayne parked his car at the end of the street around midnight and walked over to the house. Norman asked his wife to text Kelly, so she messaged: ‘Hi Kelly, It’s Sheryl your neighbour. Norman has noticed that Wayne has driven past the house a few times. Is everything ok?’ When Kelly didn’t respond, Norman called Werribee Police Station. As he was on the phone to the junior constable, Sheryl saw the ensuite light at Kelly’s house switch on, and the silhouette of Wayne’s bald head in the window.

On the phone, Norman was struggling to get the police to take him seriously. Despite him saying that he thought there was an intervention order in place, the constable dismissed his concerns, explaining that the police escorts he’d seen at Kelly’s house could have been supervising a simple property dispute. He asked Norman: ‘Can you do me a massive favour, pal, and keep an eye on the address? If the circumstances change, you notice anything untoward, or if you hear any yelling or screaming coming from that particular address, please do not hesitate calling back and I’ll send a van around.’

Three days later, after receiving a missing person’s report from Wayne’s brother, Gavin, police went to Kelly’s house. They found her car in the driveway and could hear a dog barking inside. Forcing their way in, they went up to Kelly’s bedroom and found two bodies. Kelly had been stabbed with a hunting knife, and Wayne was found kneeling on the bedroom floor, with a rope attached to the bedpost tied around his neck. There were two kitchen knives beside Kelly’s bed, and a third in the top drawer.

In his testimony to the coroner, Assistant Commissioner Cornelius was contrite, conceding to a laundry list of police failures in the lead-up to Kelly Thompson’s murder. The failure to dispatch police to Kelly’s house the night she was murdered was ‘a very significant oversight’. Police should have waited for Kelly’s business partner to arrive during that first crucial callout, and they should have interviewed the driver she disclosed the choking to, Steven Hall. It was clear there was a story to be told, he said, and the attending police had ‘a duty to inquire’. Leaving out the strangulation report on the L17 was ‘a critical omission’, and the fact that police still relied on fax machines for receiving intervention orders was akin to ‘using a carrier pigeon’. By agreeing to escort Wayne on several occasions to pick up property from Kelly’s house, police may have been used as ‘an instrument of family violence,’ he added.

In his findings, the coroner said that Kelly took ‘all the right steps’. She was obviously in fear for her life – as her mother, Wendy Thompson, told the inquest, ‘I knew she was fearful but the thought of the depth of her fear as to need three knives close to her bed shocked me.’ The coroner stopped short of finding police responsible for Kelly’s death, attributing that blame solely to Wayne. Even if police had responded to the call from Kelly’s neighbour, he said, it’s unlikely they would have been able to save her. Wendy had a different response: ‘Had [Victoria Police] responded, or shown him there were consequences for breaching those orders early on, Kelly would be alive today.

See What You Made Me Do is available here.

If you or someone you know is experiencing domestic abuse, call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732 or visit 1800RESPECT.org.au.

For 24-hour state-wide help, including emergency transport and accommodation, call:

ACT: Domestic Violence Crisis Service 02 6280 0900

New South Wales: NSW Domestic Violence Line 1800 656 463

Northern Territory: Catherine Booth House 8981 5928

South Australia: Domestic Violence and Aboriginal Family Violence Gateway Services 1800 800 098

Tasmania: Safe at Home Family Violence Response and Referral Line 1800 633 937

Queensland: DVConnect 1800 811 811

Victoria: Safe Steps Family Violence Response Centre 1800 015 188

Western Australia: Women’s Domestic Violence Helpline 1800 015 188

Men who are experiencing abuse (or are concerned about their own behaviour) can call MensLine Australia on 1300 78 99 78.

Share this post

About the author

Jess Hill is an investigative journalist and the author of See What You Made Me Do and the Quarterly Essay The Reckoning. She has been a producer for ABC Radio and journalist for Background Briefing, and Middle East correspondent for The Global Mail. Her reporting on domestic abuse has won two Walkley awards, an Amnesty International award and three Our Watch awards. See What You Made Me Do won the 2020 Stella Prize …

More about Jess Hill