News

News >

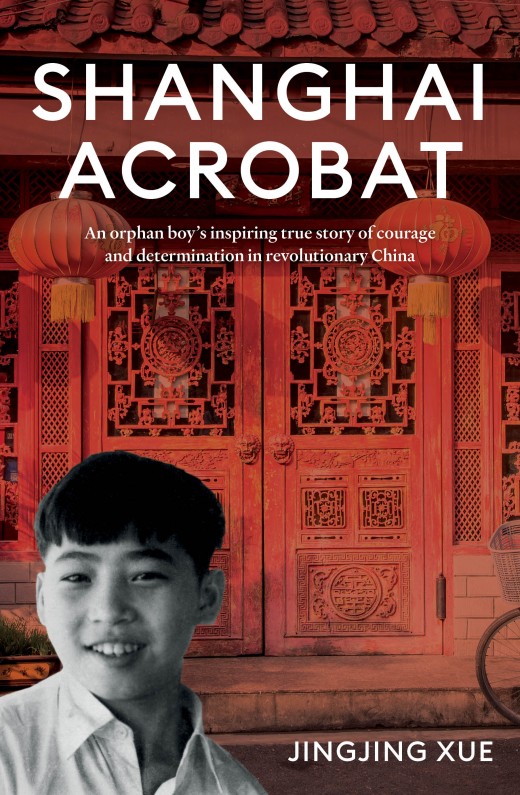

Read an extract: Shanghai Acrobat

Read an extract from Shanghai Acrobat, an orphan boy’s inspiring true story of courage and determination in revolutionary China.

‘You! … You! … Not you … You!’

The man was moving through the rows of students, coming towards me. I did not know whether I wanted him to choose me or not, as I had no idea where his decision might lead.

‘You!’

He was getting closer. I shivered, but forced back the urge to stamp my feet. I was nine years old and this place, the Youth Village, was the fifth orphanage I had lived in. It was by far the worst. The classroom, where we were standing in lines waiting for this strange man to inspect us, was on the first floor of a red brick building facing west, receiving no sun until late in the day – and for most of the year. Sometimes, we children were allowed outside between classes to find a pool of sunlight to bathe in for a few precious minutes. Mostly, we froze in the below-zero Shanghai temperatures. When it got too cold to bear, the older students would begin to stamp their feet and we would watch the teacher for his reaction. If he said nothing, we would all copy the older students. Once, in a rare show of sympathy, the teacher stopped the class and let us keep stamping until we warmed up.

‘You!’

He was close to me now. All we had been told was that he had come from the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe, which was said to be famous, but I had no idea what an acrobatic troupe did, or what ‘famous’ meant.

The man from the troupe, with one of our teachers beside him, stopped in front of me. He did not touch me, but merely swept his eyes over my body. I was the smallest child in the class. I had been an orphan since I was two years old.

‘You!’

Shanghai, 1963: My one-armed handstand with spinning rings.

Three weeks passed before the man came back. In the meantime, we went about our normal routines in the Youth Village. The main building, a red brick former church, was our dining and meeting hall. Another red brick building, forming an L with the hall, contained dormitories for boys on the ground floor, with girls a floor above. My dormitory was jam-packed with bunk beds for more than twenty boys, from nine to sixteen years of age. The air was thick with smelly feet and farts. In the dining hall we ate plain flour noodles, cooked in soup with bran, pumpkins and carrots, without any trace of meat. Hunger was constant, as was constipation. Our hopes rose when the older boys wrote a petition to request better food, but nothing came of it. If those strong older boys could achieve nothing on such an essential matter, we were all powerless.

At the end of the L-shaped building complex, next to a wall connected to the main gate of the former church, was a dirt basketball court, where in the mornings we did exercises and at dusk we played. Sometimes we flew kites, and occasionally, against the wall of this court, there would be screenings of Russian war movies such as Lenin in October and Chapaev, the favourites of the older boys, who rushed to occupy the front rows. Those boys were like my big brothers and looked after me, but after everything I had been through already, I had developed a very independent character.

I had been chosen, but for what? While I waited to find out, I learnt more about the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe. Before ‘liberation’ – the word we were taught to use for the Communist revolution that had taken control of China seven years earlier, in 1949 – acrobats, or ‘trick-players’, were from the lowest stratum of society. Only those families who could not make a living would send their children to an acrobatic troupe to learn ‘tricks’, in the hope that they would have a trade to support themselves. After liberation, the status of acrobats sank even lower. Finding students became so difficult, the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe had to turn to the orphanages.

Shanghai, 1973: Performing a balancing act on our pre-departure performance on Chinese New Year.

Three weeks after that initial visit, I was told to report to the Teaching Affairs Office, where I found myself among a group of boys and girls aged from nine to fourteen. More people from the troupe had come with the man who had done the original selection.

‘Stand still!’

Another man held a tape measure at my head and along my arms and legs.

‘Jump!’

I jumped.

‘Grip as hard as you can!’

I gripped as hard as I could.

‘Show the arch of your foot!’

I showed him the arches of my feet.

‘Let me see your face!’

I did my best to show the recruiters a pleasing face.

Nobody explained why they were doing each test. No one asked us whether we wanted to learn acrobatics, or what our interests and hobbies were. This was just a measurement process, as if we were livestock being sized up. But for what? We were not told, yet when they ordered us back to our dormitories to pack up our meagre belongings, we were just happy that we could leave. No place could be as bad as the Youth Village. And I knew how bad the orphanages of Shanghai could be.

This is an extract from Shanghai Acrobat, in bookstores now.

Share this post

About the author

Jingjing Xue was a star performer with the Shanghai Acrobatic Troupe. Considered one of China’s best acrobats, from 1961 to 1987 he performed around the world with the Shanghai Circus. He has trained performers in China and at the National Institute of Circus Arts in Melbourne. Three of his students have won gold medals in international circus competitions. Shanghai Acrobat is his first book.

More about Jingjing Xue