News

News >

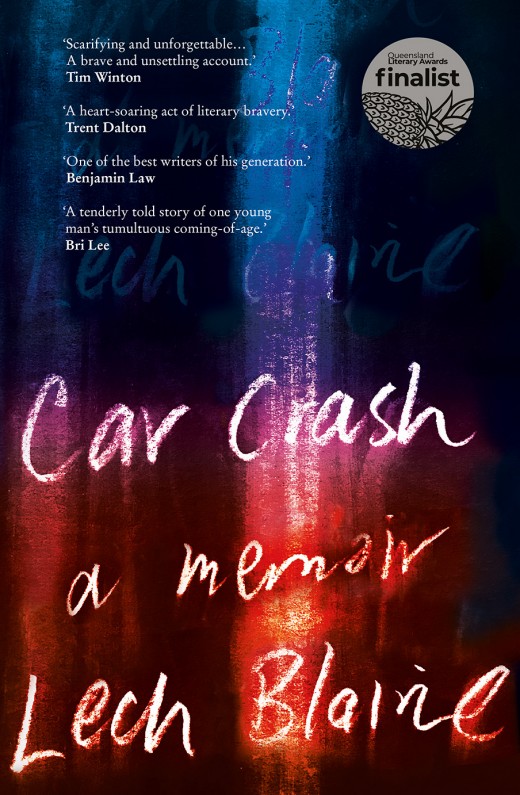

Read an extract: Car Crash

Read an extract from Car Crash, Lech Blaine’s stunning memoir about grief, perseverance and courage.

An artist doesn’t happen by accident, and neither does a larrikin. My parents met at a backyard barbeque in Ipswich, circa 1979.

Mum was a nervous bookworm and a financial clerk for a department store – a bush poetry enthusiast with a permed mullet who shunned make-up, dresses and jewellery. She was allergic to public speaking and physical exercise.

She said, ‘Slow and steady finishes the race.’

She said, ‘You’re not playing for sheep stations.’

She said, ‘You don’t need to win anything to have fun.’

Dad was a 130-kilogram cab driver with a mullet and a handlebar moustache who had never read a novel in his life. A rugby league coach and a former professional gambler, he let off steam at weekends by punting large sums on thoroughbreds and greyhounds. He peppered his enemies with sledges and sculled beer from a saucepan. Beating people was the meaning of life.

He said, ‘If you’re not first, you’re finished.’

He said, ‘You need to risk it to get the biscuit.’

He said, ‘Never trust a bloke who doesn’t drink.’

I have her to thank for the vocabulary and him for the ego.

Both dropped out of high school before Grade Nine to support their families. Dad dreamed of being a rich businessman. Mum dreamed of raising a big family.

After tying the knot, Mum suffered six miscarriages. The pragmatic battlers became foster carers instead and relocated to the bush in pursuit of a cut-price Australian dream. By autumn 1991, they’d leased three rundown pubs across country Queensland and accepted six permanent foster children under the age of twelve. This brood sometimes blew out to ten or eleven.

‘One more try,’ said Mum, who had started taking a shady oestrogen-replacement drug from a rogue fertility doctor at the age of thirty-eight. It was manufactured from the urine of pregnant mares.

Secretly, she daydreamed about a baby girl named Amy Blaine, another shy female, and a rare example of her personal preference prevailing over that of her cocksure husband.

‘Let’s hope the piss came from Phar Lap’s granddaughter,’ said Dad, craving a biological son who could run the hundred metres in under ten seconds.

On 22 January 1992, I arrived to great fanfare, surprisingly alive, a miracle child with a full-blown god complex. My mother emerged from a C-section to see her first breathing baby wrapped in a pink sheet. The hospital had run out of the blue ones it used for boys.

‘It’s a girl!’ she cried.

‘Nope,’ said Dad. ‘It’s a boy.’

According to my eldest brother, Trent, it went back and forth like this: It’s a girl! It’s a boy! It’s a girl! It’s a boy!

Mum gestured desperately. ‘Why would they give a pink sheet to a boy?’

Dad unwrapped the sheet to expose the only evidence that mattered, his prize for a lifetime’s supply of bad luck. ‘My kid’s got a dick!’ he roared.

My father won naming rights and named me after his doppelgänger, Lech Wałęsa, a fat battler with a thick moustache. Lech was a revolutionary trade unionist and the freshly elected president of Poland. My pop John had been a blacksmith on the Ipswich railway and vice-president of the Queensland Ironworkers Union – this was why a bartender in Wondai dedicated his long-awaited heir to Eastern Europe’s great emancipator.

At the age of sixteen, my father had shattered his hip at the Ipswich meatworks and spent six months in hospital. He never played rugby league again. That bitter winter, Dad’s brother George won the Bulimba Cup for Ipswich as a goalkicking fullback, and his sister Rita gave birth to a blonde bombshell named Allan Langer.

After Allan dropped out of high school, my mother got him his first job, as a furniture removalist, while my father was still getting laughed out of clubhouses across Ipswich for suggesting his 166-centimetre nephew would play football for Queensland and, one day, Australia. ‘Are your eyes painted on?’ they said. ‘He’s a friggin’ midget!’

Dad had a history-making chip on his shoulder. He was pissed off about missed opportunities, and craved greatness in the next generation of the Blaine bloodline. Allan Langer was a part-time athlete and full-time council worker when selectors picked him to play the first game of the 1987 State of Origin. ‘Alfie’ starred from the get-go, picking up Man of the Match in the series decider.

Nineteen ninety-two was indisputably the happiest year of my father’s life. On the fourth Sunday of spring, Allan Langer captained the Brisbane Broncos to the first of consecutive premierships against the St George Dragons, whipping the cream of Sydney’s establishment.

‘You little beaut-ay!’ Dad sang while feeding me mashed bananas and himself a Johnnie Walker and Diet Coke. That scruffy Australian battler was the father of a son and the uncle of a gun.

My parents sold the lease of the Wondai Hotel. Mum got paid a few dollars an hour to be a 24/7 psychologist to six children. Dad got a part-time job as a bartender at the Wondai Bowls and Golf Club. They ploughed their life savings into a cheap acre of red dirt, where they planted a removable home that used to be a maternity hospital.

Every Sunday for a month, my brothers filled the tray of a one-tonne Falcon ute with turf from the Murgon Meatworks. My father drove the cargo home so they could mask the drought-stricken earth around the house. He had thick forearms and tanned, muscly calves. ‘Mowing the lawn’s better than watchin’ porn,’ he’d say.

At night, Mum and Dad checked my cot as though it harboured a million-dollar bill. During the day, six overprotective foster siblings studied every burp, piss, fart and shit with wonder and unspoken envy. ‘Mum,’ they cried, fighting over me. ‘It’s my turn to hold him!’

The slew of days and nights turned me into a toddler, but my novelty didn’t wear off. I remember an island of green grass in an ocean of red dirt. The sound of buzzing flies and squeal-ing springs on a trampoline. The scent of beer on Dad’s thick, tickling fingers, and the whiff of menthol cigarettes from Mum’s insistent kisses.

‘Mummy didn’t have any babies come from her tummy until a little boy named Lech Jack Thomas,’ she cooed, a lullaby that never grew old. ‘Everyone was so happy the day that Bubby Jack was born, but especially Mummy and Daddy. He made up for the sad times, because his face made Mummy feel warm and fuzzy in the tummy.’

The adoration was unsustainable. I’d never be loved so unconditionally again. This set me up for daily heartbreaks in the real world, where no one responded with quite the same level of amazement.

We moved to Toowoomba in 1996. My father bought a cheap hotel lease. My mother – who didn’t want to leave the bush – ferried six foster children in a small bus. Dad and I drove separately. I sat in the front passenger seat of a black Ford Falcon with a moon roof. We passed farms that hadn’t yet been subdivided, and the slight bend in the highway where my life would spiral out of control.

Toowoomba was treated to its wettest year since 1893. I remember pissing rain and hissing winds. The Country Club Hotel was stubbornly rundown, a fitting reflection of the suburb, Mort Estate, which was filled with boarding houses and council flats. The customers were tradies and railway workers with loose bowels and foul mouths. They drank cheap schooners until the sun went down. Then the shot glasses came out and their red necks got hot underneath blue collars.

‘Oi, two-pot screamer,’ my father declared to a man speaking lewdly to the barmaid during happy hour. ‘Pull your head in, before I do it for ya.’

I was forever running from the publican to the bookkeeper. In the office, my mother kept a secret stash of sweeties: milkos, strawberry and creams, chicos and pineapples. She raised seven kids while speed-reading half a dozen novels a week, and could recite ‘The Man from Snowy River’ and ‘Clancy of the Overflow’ verbatim, like a bush poetry jukebox: ‘. . . the hurrying people daunt me, and their pallid faces haunt me, as they shoulder one another in their rush and nervous haste.’

We had matching hazel green eyes and generalised anxiety, but my mother was never the same after moving to the Big Smoke. She didn’t like the density of bodies and the condescen-sion of rich agricultural types from old money. During the wettest year since Federation, mosquitoes provided a convenient alibi for clinical depression – she blamed lethargy on Ross River fever.

Although Dad had the gift of the gab, he was minimalist, not a chatterbox like me.

He said, ‘Life’s a mixed bag of shit.’

He said, ‘Death’s a one-horse race.’

He said, ‘Pity’s the last straw of pride.’

My father’s poisons of choice included steak-and-bacon sandwiches, snags, rissoles, T-bones, lamb cutlets, rib fillets, deep-fried potatoes, meat pies and sausage rolls. I never saw him eat so much as a chicken nugget or a fish finger, such was his fidelity to red meat.

‘Chicken’s for women,’ he told me. ‘Fish is for Christians.’

‘What about salad?’ I asked.

‘Do I look like a friggin’ guinea pig?’

Upstairs, when he took a rare break from the bar, a drape of flab hung from the bottom of his Jackie Howe singlets, worn with footy shorts and thongs. His heels cracked under so much weight and yellowed from the application of Rawleigh’s Antiseptic Salve, giving him a perpetually sterile scent. For man and beast, it said on the tin.

One Sunday afternoon, the licensee evicted a trio of skinheads because a member of the gang was underage. A few hours later, I was bouncing a football around the plastic-wrapped pal-lets of XXXX Gold and Victoria Bitter. The nu-metal enthusiasts returned with reinforcements.

‘Fuck you and your grandson,’ said one.

I was five. My father was nearly fifty. Half a dozen heavily tattooed teenagers stood on the footpath.

‘Say that to my face, ya Nazis,’ he said, so they did.

Dad went for a quick knockout but missed, before tripping backwards on a gutter. The punks kicked the shit out of him within touching distance of me. A plasterer rushed out from the bar and king-hit the ringleader.

Afterwards, we sat in the coldroom waiting for the police to make a routine visit. My father applied a cool can of VB to a bleeding eye socket. I was mesmerised not by violence, but by the sight of a humiliated tough guy.

‘I’d love to see them throw a punch one on one,’ he said. ‘A bunch of gutless wonders.’

That year, he suffered a life-threatening heart attack. In the hospital’s smoking area, my mother’s hands were shaking. ‘What’s wrong, Mum?’ I asked.

‘I’m worried, honey. Dad’s heart is in a bad way.’

I’d never set foot inside a church, but I spent the next week praying to God and negotiating Dad’s entry to heaven.

‘What happens after we die?’ I asked him.

‘Sweet stuff-all,’ he said. ‘We’ll be meat for the worms.’

Dad came home in a hospital bracelet, compression socks and with fresh scars on a shaved chest. I whipped myself into panic about the fact one day he’d be dead. The interesting thing about my routine retreat into the master bedroom between midnight and sunrise is that my tough-as-nails father didn’t tell me to grow some balls.

‘You’re a big boy now,’ said my mother.

But Dad pulled my small body into a stomach that just kept going, a grizzly bear harbouring a koala. ‘Leave him alone,’ he said. ‘He isn’t doing you any harm.’ I knew that I’d rather cease breathing than be alive without him.

Car Crash: A Memoir is in bookstores now.

Share this post

About the author

Lech Blaine is the author of the memoir Car Crash and the Quarterly Essays Top Blokes and Bad Cop. He is the 2023 Charles Perkins Centre writer in residence. His writing has appeared in Good Weekend, Griffith Review, The Guardian and The Monthly. His latest book is Australian Gospel.

More about Lech Blaine