News

News > Extract

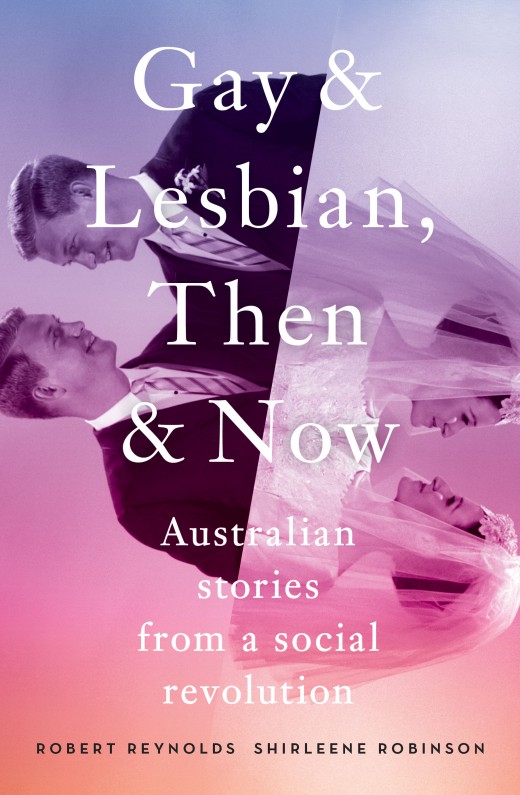

Read an extract from Gay and Lesbian, Then and Now: Australian Stories from a Social Revolution

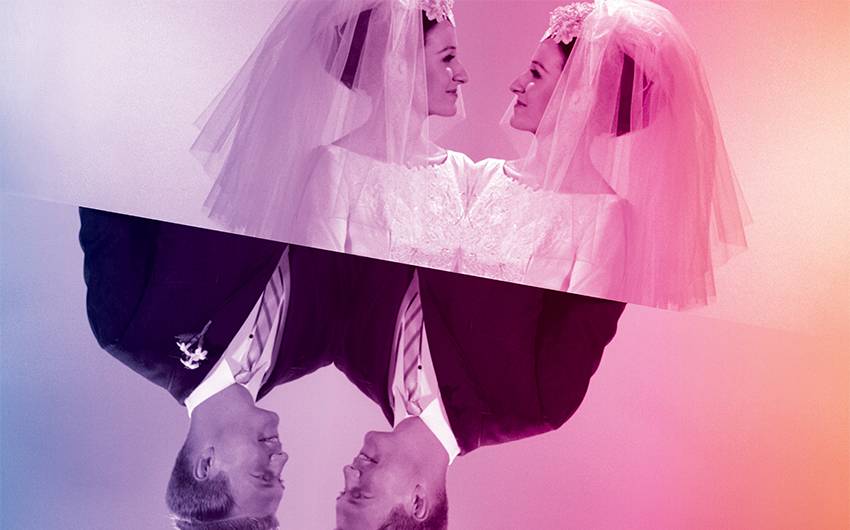

Over recent decades, Australia has undergone a quiet but remarkable revolution.

Over recent decades, Australia has undergone a quiet but remarkable revolution. For much of its history, intimate relationships between those of the same sex were hidden, criminalised, classified and stigmatised. Today, gay men and lesbians are increasingly recognised as full and equal citizens. Countless television shows feature gay and lesbian characters, newspapers carry columns about marriage equality, and many same-sex couples nonchalantly show affection in the city and country alike. Traditionally gay precincts such as Sydney’s Oxford Street and Melbourne’s Commercial Road are on the decline as gay consumers feel less of a need for predominantly homosexual spaces. Changing social attitudes towards homosexuality are reflected in polls. In a 1967 survey, only 22 per cent of Australians supported the legalisation of homosexual acts. In 2014 a Crosby Textor poll found an overwhelming 72 per cent of Australians supported the right of same-sex couples to marry.

Clearly, something extraordinary is happening: a social revolution perhaps without parallel in Australian history. But what have been the experiences of the men and women at the heart of this change? What have gay and lesbian lives been like as broader social attitudes have undergone such an evolution? How has change been experienced by those from different generations? These were some of the questions we hoped to answer when we embarked on recording the lives of sixty gay and lesbian Australians from around the country, in collaboration with the National Library of Australia. We wanted to understand how the past was remembered today, and how different or similar the experiences of young lesbians and gay men are to those of previous generations.

Our primary interest was in what social change has been like for ‘ordinary’ Australian gay men and lesbians – not public figures or activists, but those who have lived workaday lives. These ordinary men and women may participate sporadically and peripherally in campaigns for social change, but they don’t take on leadership roles. This does not mean that they don’t play a role in social change, but that they do so through their personal relationships and the ebb and flow of everyday life, rather than through organised activism. We suspected – and confirmed – that the quiet revolution has been carried out within the lounge rooms of suburban Australia, at beachside barbecues, and in country towns as much as through public demonstrations, media coverage and in gay ‘ghettos’ such as Oxford Street.

But how to get to these stories of everyday, ordinary lesbian and gay lives? We decided that the most evocative way was to speak directly and intimately with the women and men most affected by the revolution in social attitudes. In the course of interviewing them, our research team, lugging a recorder in a bulky black briefcase, crisscrossed Australia, determined to cover as much terrain as possible: from coastal Denmark in the south of Western Australia, to Darwin in the Northern Territory. We visited Dodges Ferry in Tasmania before heading to Magnetic Island, off the coast of Townsville. Wherever we went, we were greeted with warmth and generosity, drank many cups of tea and coffee, and heard compelling and often very moving stories of ordinary Australians living through remarkable times. The oldest person we interviewed was born in 1921 and the youngest was born seventy-one years later, in 1992.

As we travelled, we saw social shifts in Australia play out in sometimes unexpected ways. We watched marriage equality campaigners being warmly greeted by shoppers in a Rockhampton shopping centre. We saw two elderly men, clearly a couple, holding hands as they walked through the main street of a small New South Wales country town. We saw federal politicians spend six hours debating whether there should be a parliamentary free vote on marriage equality and ultimately decide against this. We also heard accounts of homophobic abuse and violence, of family rejection and very real struggles with suicidal thoughts. And as we finished writing this book in early 2016, we watched in dismay a concerted effort by the Christian Right to undermine the wellbeing of LGBTI students in schools. The pace and impact of the quiet revolution is uneven.

Debate is ongoing in the gay and lesbian community about the costs and benefits of integrating with the mainstream. There are those who lament the loss of a certain radicalism. Others enthusiastically welcome the assimilation of gay men and lesbians into mainstream culture and agitate hard for everyday rights like marriage. While no gain is without losses, we suspected – and our interviews confirmed – that the increased capacity of homosexual Australians to live ‘ordinary’ lives with the same possibilities as heterosexual Australians was a positive development.

In 1986 Garry Wotherspoon published a classic collection of gay men’s life stories under the title Being Different. In 2016 we feel that many lives are no longer so different – they are becoming ordinary. This question of ordinariness – and the way it allows individuals to live full, happy, rich lives – is what we set out to explore and capture in Gay & Lesbian, Then & Now.

From the extensive cohort interviewed, we selected thirteen individuals. While they cannot represent the entire experience of gay and lesbian Australians, we believe their stories reveal some of the significant shifts that have taken place in ordinary lives over the past eighty years. We deliberately sought to include people from a range of social and racial backgrounds, and those who grew up or have lived in rural locations. The interviews touched on issues as diverse as ethnicity and gender, personal temperament, family dynamics, class, religion, sex and intimacy.

While there is overlap between the different generations, we have broadly divided the book into three sections that we think represent significantly different life experiences. In Part I we explore the lives of Merv and Nola, who were born in 1933 and 1944 respectively and came of age well before the gay liberation movement and feminist movement of the 1970s. Those born between the early 1920s and 1945 are often described as ‘The Lucky Generation’ or ‘The Builders’, and sometimes as ‘The Silent Generation’. We did not think these names representative of gay and lesbian experience, so we settled on another descriptor: ‘The Veterans’. In Part II, ‘The Baby Boomers and Generation X’, we meet three women and two men who reached maturity in the 1970s or ’80s and were significantly affected by feminism and gay liberation. In Part III, ‘The Millennials’, we consider the life stories of four younger men and women whose sense of identity has been forged at a time when gay and lesbian people have never been more visible, although a distinct physical gay and lesbian culture appears to be on the wane even as it migrates online. And in the conclusion, we meet Alex, a young woman in Melbourne living a full, contented and relatively ordinary life as a lesbian.

Taken together, these thirteen lives reveal a remarkable eight decades of change and point the way, we hope, to a more equal, transformative future.

Share this post

About the authors

Shirleene Robinson is Vice Chancellor’s Innovation Fellow in MHPIR at Macquarie University.

More about Shirleene Robinson

Robert Reynolds is Associate Professor in the department of Modern History, Politics and International Relations (MHPIR) at Macquarie University.

More about Robert Reynolds