News

News > Extract

Read an extract from Bob Ellis: In His Own Words

When veteran author, speechwriter, scriptwriter, director and political commentator Bob Ellis died from liver cancer at the age of 73, Australia mourned the loss of one of its finest literary raconteurs. During his long and prodigous career, Ellis wrote over twenty books, fifty-five screenplays, two hundred poems, five hundred political speeches, a hundred songs and two thousand film reviews. For nine months before his death, he chronicled his battle with cancer on his popular Table Talk blog where he also found time to heap scathing appraisals on the Abbott and Turnbull governments, as well as share delightful discourses on film, theatre and travel.

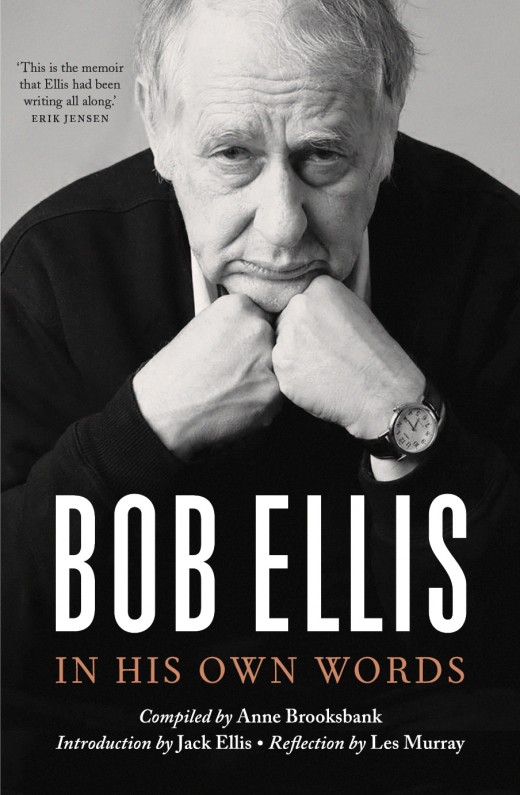

We were delighted to launch Bob Ellis: In His Own Words last Thursday, 6 October at The Theatre Bar in Sydney alongside his widow Anne Brooksbank, his son Jack Ellis, the Hon. Bill Shorten MP (pictured) and many devout Ellis admirers. The book – a bountiful treasury of Ellis’s celebrated and much-loved essays, speeches, diaries and scripts – was compiled by Brooksbank herself and features an introduction by Jack Ellis in addition to a reflection by Les Murray. We are enormously proud to have published this celebration of an inimitable wordsmith's life and legacy, and would like to thank all who contributed to making the night such a great success.

Scroll down to read an extract from Bob Ellis: In His Own Words or to buy the book online.

'MY SYDNEY'

The inner Sydney I knew when I came down on the old steam North Coast Mail to go to university is there no longer. The Sydney of the Hasty Tasty and Vadims and Lorenzinis and the Hotel Australia and the Bondi trams, I was too young and fierce and shy to appreciate then, and I mourn it now. Ancient Sydney, it will soon be known as. Like the foot-ruler and the pound, it will always be more real to me than the bland, glass-fronted fatuity that followed. But in these gleaming ruins there are a few pickings, and out of these I eke my present life.

My life slouches down two worlds, one green and watery and the other close and polluted. I love them both, according to their lights, as I do my family and my scabrous vagabond youth. They are what remains of the ancient bohemian Cross, and what still shines and dreams in the waters and forests of the northern peninsula.

In the Cross I can go at four a.m. to the Jaffle Joint and warmly breakfast on cremated cheese and bacon and be back in my tight little flat at in time for Danger Man on Channel 9, my favourite program of all. In Palm Beach I can wake screaming at three a.m. to the rumble of possums across my tin roof, get up trembling, read a book until five ... and then watch Danger Man. In either place, my little son will wake me at six, then I go back to sleep till eight or nine. At which point I rise and begin to procrastinate writing. Procrastination takes up most of my day. Eventually I get bored into useful activity, and I write exceedingly fast and am always two days over the deadline. My editors, directors, producers and creditors hate me very much.

Palm Beach is the best place in the world to work. The prospects of water and sailboats and distant forests and winking lighthouse move me to easy eloquence, and my scripts are always fifty pages too long. I write in bed in a green sleeping-bag with a sharpened pencil, or with a typewriter on a desk overlooking a view. Like most people in Palm Beach, I overlook the best view in Australia. Like most people in Palm Beach, I will never leave, unless my little son gets killed on the roaring roadway underneath our cliff, or by a landslide, or by ticks or snakes. Or the possums increase my nightmares beyond endurance. It is hard to know what to do about possums: their hands and their eyes are so like human beings’, but murder is much on my mind. They live in our roof and in certain seasons fornicate abrasively with screeches and thumps at hours more common in Kings Cross. They also live on our duck food, and therefore multiply exceedingly. Our two pet ducks stay awake all night too and hiss deafeningly at every form of life. I came to Palm Beach in quest of a good night’s sleep. Perhaps there is no such thing.

It is very quiet in the Cross, and sleep there is wonderful. So is drinking at the Strand and at the East Sydney with famous criminals and actors, and eating alone at Pinocchio’s, while reading the Listener and Private Eye, the one dish that is not on the menu, their wonderful vegetarian pizza, as I have every week for seven years now; and script conferences over coffee at the Moka, and walks up and down the strip-club district among the whores – ‘No, thank you, ma’am’ is the response I find they most appreciate – and brunch with ice water at the Bourbon and Beefsteak Bar, out of whose windows it seems the Cross is still a beautiful place, and perhaps it is. Perhaps I am growing old. I was thirty-seven on Thursday last, and Annie for my birthday gave me a kitchen implement, something she would not have dared when I was young and furious still, and she was not yet my wife.

I am frightened of too much happiness, like most writers, and so feel threatened by the Peninsula. With its barbecues and nudity and sailboats and restaurants and saunas and marijuana, I could be quite corrupted into pot-bellied contentment. I am even considering joining the golf club. I played golf once, in Lismore. Went round in ninety-three. Nine holes. Kismet, however, is dealing with this dread possibility of happiness. Many film directors are moving into the neighbourhood, lowering property values and glaring at me across the supermarket ...

First published in the Daily Mirror, May 1979.